-

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion India Launch Set for April 2; Design, Key Features Revealed24 March 2025

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion India Launch Set for April 2; Design, Key Features Revealed24 March 2025 -

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion Design, Display Details Teased Ahead of Upcoming India Launch21 March 2025

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion Design, Display Details Teased Ahead of Upcoming India Launch21 March 2025 -

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion India Launch Date Leaked; Said to Get MediaTek Dimensity 7400 SoC, 5,500mAh Battery19 March 2025

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion India Launch Date Leaked; Said to Get MediaTek Dimensity 7400 SoC, 5,500mAh Battery19 March 2025 -

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion India Launch Teased; Design Renders Surface Online13 March 2025

Motorola Edge 60 Fusion India Launch Teased; Design Renders Surface Online13 March 2025 -

Motorola Edge 60 Series, Moto G56 and Moto G86 Price, Colours, Storage Options Leaked10 March 2025

Motorola Edge 60 Series, Moto G56 and Moto G86 Price, Colours, Storage Options Leaked10 March 2025

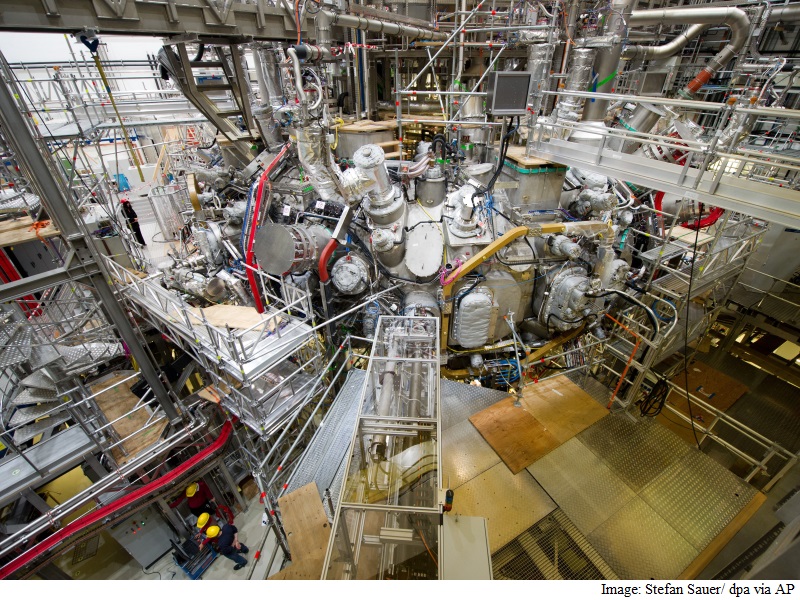

Scientists to Inject Fuel in Experimental Fusion Device

Advertisement

Scientists in northeast Germany were poised to flip the switch Wednesday

on an experiment they hope will advance the quest for nuclear fusion,

considered a clean and safe form of nuclear power."

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Greifswald planned to inject a tiny amount of hydrogen and heat it until it becomes a super-hot gas known as plasma, mimicking conditions inside the sun.

It's part of a world-wide effort to harness nuclear fusion, a process in which atoms join at extremely high temperatures and release large amounts of energy.

Advocates acknowledge that the technology is probably many decades away, but argue that - once achieved - it could replace fossil fuels and conventional nuclear fission reactors.

Construction has already begun in southern France on ITER, a huge international research reactor that uses a strong electric current to trap plasma inside a doughnut-shaped device long enough for fusion to take place. The device, known as a tokamak, was conceived by Soviet physicists in the 1950s and is considered fairly easy to build, but extremely difficult to operate.

The team in Greifswald, a port city on Germany's Baltic coast, is focused on a rival technology invented by the American physicist Lyman Spitzer in 1950. Called a stellarator, the device has the same doughnut shape as a tokamak but uses a complicated system of magnetic coils to achieve the same result.

The Greifswald device should be able to keep plasma in place for much longer than a tokamak, said Thomas Klinger, who heads the project.

"The stellarator is much calmer," he said in a telephone interview. "It's far harder to build, but easier to operate."

Known as the Wendelstein 7-X stellarator, or W7-X, the 400-million-euro ($435-million) device was first fired up in December using helium, which is easier to heat. Helium also has the advantage of "cleaning" any minute dirt particles left behind during the construction of the device.

David Anderson, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin who isn't involved in the project, said the project in Greifswald looks promising so far.

"The impressive results obtained in the startup of the machine were remarkable," he said in an email. "This is usually a difficult and arduous process. The speed with which W7-X became operational is a testament to the care and quality of the fabrication of the device and makes a very positive statement about the stellarator concept itself. W7-X is a truly remarkable achievement and the worldwide fusion community looks forward to many exciting results."

While critics have said the pursuit of nuclear fusion is an expensive waste of money that could be better spent on other projects, Germany has forged ahead in funding the Greifswald project, which in the past 20 years has reached €1.06 billion euros if staff salaries are included. Chancellor Angela Merkel, who holds a doctorate in physics, is expected to attend Wednesday's event, which happens to be in her constituency.

Over the coming years W7-X, which isn't designed to produce any energy itself, will test many of the extreme conditions such devices will be subjected to if they are ever to generate power, said John Jelonnek, a physicists at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany.

Jelonnek's team is responsible for a key component of the device, the massive microwave ovens that will turn hydrogen into plasma, eventually reaching 100 million degrees Celsius (212 million Fahrenheit).

Compared to nuclear fission, which produces huge amounts of radioactive material that will be around for thousands of years, the waste from nuclear fusion would be negligible, he said.

"It's a very clean source of power, the cleanest you could possibly wish for. We're not doing this for us, but for our children and grandchildren."

For the latest tech news and reviews, follow Gadgets 360 on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News. For the latest videos on gadgets and tech, subscribe to our YouTube channel. If you want to know everything about top influencers, follow our in-house Who'sThat360 on Instagram and YouTube.

Further reading:

Fusion, Fusion reactor, Greifswald, Max Planck Institute, Nuclear Fusion, Science, Stellarator

Advertisement

![Gadgets 360 With Technical Guruji: Ask TG [ March 22, 2025]](https://c.ndtvimg.com/2024-12/5s52e4k_-ask-tg_640x480_14_December_24.jpg?downsize=180:*)