- Home

- Science

- Science News

- Nasa's Spitzer Space Telescope Finds Planet 13,000 Light Years Away

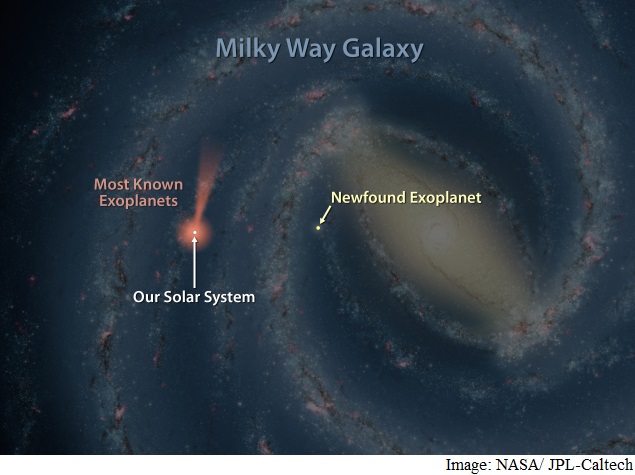

Nasa's Spitzer Space Telescope Finds Planet 13,000 Light Years Away

"We do not know if planets are more common in our galaxy's central bulge or the disk of the galaxy which is why these observations are so important," said Jennifer Yee of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

The discovery demonstrates that Spitzer from its unique perch in space can be used to help solve the puzzle of how planets are distributed throughout our flat, spiral-shaped Milky Way galaxy.

Spitzer circles our Sun and is currently about 207 million km away from Earth. When Spitzer watches a microlensing event simultaneously with a telescope on Earth, it sees the star brighten at a different time, due to the large distance between the two telescopes and their unique vantage points.

A microlensing event occurs when one star happens to pass in front of another and its gravity acts as a lens to magnify and brighten the more distant star's light.

If that foreground star happens to have a planet in orbit around it, the planet might cause a blip in the magnification. This technique is generally referred to as parallax.

"Spitzer is the first space telescope to make a microlens parallax measurement for a planet," Yee added.

In the case of the newfound planet, the duration of the microlensing event happened to be unusually long about 150 days. Knowing the distance allowed the scientists to also determine the mass of the planet, which is about half that of Jupiter.

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Realme C83 5G

- Nothing Phone 4a Pro

- Infinix Note 60 Ultra

- Nothing Phone 4a

- Honor 600 Lite

- Nubia Neo 5 GT

- Realme Narzo Power 5G

- Vivo X300 FE

- MacBook Neo

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- Tecno Megapad 2

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Tecno Watch GT 1S

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)