- Home

- Science

- Science News

- Acclaimed Scientist Claudia Alexander Passes Away at Age 56

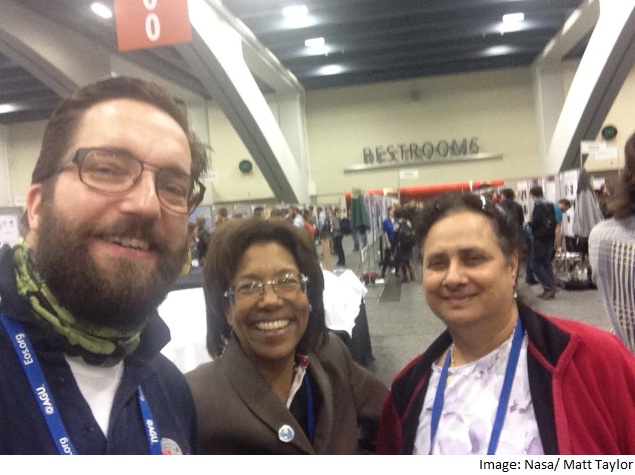

Acclaimed Scientist Claudia Alexander Passes Away at Age 56

Claudia Alexander, a brilliant, pioneering scientist who helped direct both Nasa's Galileo mission to Jupiter and the international Rosetta space-exploration project, has died at age 56.

Pasadena's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where Alexander worked as the US leader on the Rosetta Project, announced her death Thursday. JPL officials said she died Saturday after a long battle with breast cancer.

As word of her passing spread through the science community, tributes poured in.

"Claudia brought a rare combination of skills to her work as a space explorer," said Charles Elachi, JPL's director. "Of course, with a doctorate in plasma physics, her technical credentials were solid. But she also had a special understanding of how scientific discovery affects us all, and how our greatest achievements are the result of teamwork."

An acclaimed scientist who conducted landmark research on the evolution and interior physics of comets, Jupiter and its moons, solar wind and other subjects, Alexander authored or co-authored more than a dozen scientific papers.

The University of Michigan, from which she earned her doctorate, named her its Woman of the Year in 1993.

She was the last project manager for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Galileo mission, in which twin spacecraft launched in 1989 made an unprecedented trip to Jupiter, using the Earth's and the planet Venus' gravity to propel themselves there. Along the way they provided unprecedented observations of the solar system.

At the time of her death Alexander was project manager for the United States' involvement in the international Rosetta Project, which marked the first time a spacecraft rendezvoused with a comet.

Born in Canada and raised in Northern California's Silicon Valley, she joined JPL soon after completing graduate school.

She had originally planned on becoming a journalist but her parents steered her in another direction, insisting she pursue something that would better serve society.

"My parents blackmailed me," she once said. "I really wanted to go to the University of California at Berkeley, but my parents would only agree to pay for it if I majored in something useful like engineering. I hated engineering."

After she won an engineering internship to Nasa's Ames Research Institute, and her boss there discovered she was spending most of her time sneaking over to the space building, he sent her there. A career as a renowned space scientist had been born.

Still, the friendly, outgoing scientist wanted it known she was not strictly a science nerd.

"I'm not a brilliant white-coated Jimmy Neutron trapped in a lab," she once told her alma mater's Michigan Engineer magazine, making reference to the kid-scientist cartoon character.

She loved horseback riding, she said, as well as camping, hanging out in coffee houses and writing science fiction.

"When I was in graduate school, I went horseback riding every Sunday in the winter, and I got so I lived for that," she recalled.

Still, she added that her favorite college memory was "staying up all night with friends arguing about which one of us was going to do the most for mankind with the research we were doing."

JPL officials said two memorial services are planned, one in Los Angeles on July 25 and another in San Jose on Aug. 8.

Information on survivors was not immediately available.

For the latest tech news and reviews, follow Gadgets 360 on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News. For the latest videos on gadgets and tech, subscribe to our YouTube channel. If you want to know everything about top influencers, follow our in-house Who'sThat360 on Instagram and YouTube.

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025

- ChatGPT

- Redmi Note 14 Pro+

- iPhone 16

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Moto G15 Power

- Moto G15

- Realme 14x 5G

- Poco M7 Pro 5G

- Poco C75 5G

- Vivo Y300 (China)

- HMD Arc

- Lava Blaze Duo 5G

- Asus Zenbook S 14

- MacBook Pro 16-inch (M4 Max, 2024)

- Honor Pad V9

- Tecno Megapad 11

- Redmi Watch 5

- Huawei Watch Ultimate Design

- Sony 65 Inches Ultra HD (4K) LED Smart TV (KD-65X74L)

- TCL 55 Inches Ultra HD (4K) LED Smart TV (55C61B)

- Sony PlayStation 5 Pro

- Sony PlayStation 5 Slim Digital Edition

- Blue Star 1.5 Ton 3 Star Inverter Split AC (IC318DNUHC)

- Blue Star 1.5 Ton 3 Star Inverter Split AC (IA318VKU)