- Home

- Others

- Others News

- Web attackers point to cause in WikiLeaks

Web attackers point to cause in WikiLeaks

By Noam Cohen, The New York Times | Updated: 5 June 2012 02:22 IST

Click Here to Add Gadgets360 As A Trusted Source

Advertisement

They got their start years ago as cyberpranksters, an online community of tech-savvy kids more interested in making mischief than political statements.

But the coordinated attacks on major corporate and government Web sites in defense of WikiLeaks, which began on Wednesday and continued on Thursday, suggested that the loosely organized group called Anonymous might have come of age, evolving into one focused on more serious matters: in this case, their definition of Internet freedom.

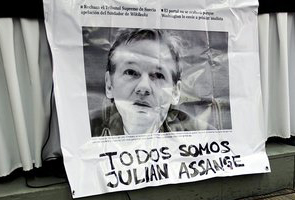

While the attacks on such behemoths as MasterCard, Visa and PayPal were not nearly as sophisticated as some less publicized assaults, they were a step forward in the group's larger battle against what it sees as increasing control of the Internet by corporations and governments. This week they found a cause and an icon: Julian Assange, the former hacker who founded WikiLeaks and is now in a London jail at the request of the Swedish authorities investigating him on accusations of rape.

"This is kind of the shot heard round the world -- this is Lexington," said John Perry Barlow, a co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil liberties organization that advocates for a freer Internet.

On Thursday, the police in the Netherlands took the first official action against the campaign, detaining a 16-year-old student in his parents' home in The Hague who they said admitted to participating in attacks on MasterCard and Visa. The precise nature of his involvement was unclear, but in past investigations, the authorities have sometimes arrested those unsophisticated enough not to cover their tracks on the Web.

Meanwhile, a lawyer for Mr. Assange, 39, said he strongly denied that he had encouraged any attacks on behalf of WikiLeaks.

"It is absolutely false," the lawyer, Jennifer Robinson, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in London on Thursday. "He did not make any such instruction, and indeed he sees that as a deliberate attempt to conflate hacking organizations" with "WikiLeaks, which is not a hacking organization. It is a news organization and a publisher."

Although Anonymous remains shadowy and without public leaders, it developed a loose hierarchy in recent years as it took on groups as diverse as the Church of Scientology and the Motion Picture Association of America.

The coordination and the tactics developed in those campaigns appeared to make this week's attacks more powerful, allowing what analysts believe is a small group to enlist thousands of activists to bombard Web sites with traffic, making them at least temporarily inaccessible. Experts say the group appears to have used more sophisticated software this time that allowed supporters to repeatedly visit the sites at a specific time when the command was given.

The Twitter account identified with the Anonymous movement contained messages with little more than the words "Fire now."

The attacks thus far have been of limited effect, shutting down the MasterCard Web site, not its online transactions.

But to security experts and people who have tracked or participated in the Anonymous movement, they indicated a step forward for cyberanarchists railing against the "elites" -- corporations and governments with power over both the machinery and, critics increasingly argue, the content on the Web.

"In the past, Anonymous made quite a lot of noise but did little damage," said Amichai Shulman, chief technology officer at Imperva, a California-based security technology company. "It's different this time around. They are starting to use the same tools that industrial hackers are using."

Despite the name, Anonymous can be found in many locations and formats. Members converse in online forums and chat rooms where friendships and alliances often build.

"It's the first place I go when I turn on my computer," said one Anonymous activist, reached on an online chat service, who did not want to be named discussing the structure of the organization.

Groups of these friends, who form new conversations, or threads, sometimes decide on a topic or an issue that they feel is deserving of more attention, the activist said.

"You post things, discuss ideas and that leads to putting out a video or a document" for a campaign. In the case of WikiLeaks, the activist said, it appears that two groups decided almost simultaneously to mount a concerted effort against the site's enemies.

"I got e-mailed these two links on Sunday or Monday," he said. Denouncing "what's being done to Julian and WikiLeaks," he said, he decided to join in.

These ideas bubble up, but ultimately a small group decides exactly what affiliated site should be attacked and when, according to a Dutch writer on the Anonymous movement, who writes a blog under the name Ernesto Van der Sar. There is a chat room "that is invite only, with a dozen or so people," he said, that pick the targets and the time of attack.

He described the typical Anonymous member as young; he guessed 18 to 24 years old.

While Anonymous has recently had success with attacks on sites related to copyright infringement cases, the WikiLeaks cause has brought a much greater intensity to its efforts.

The campaigns are part of Operation Payback, created in the summer to defend a file-sharing site in Sweden that counts itself part of the mission of keeping the Internet unfettered and unfiltered and that was singled out by the authorities.

"We could move against enemies of WikiLeaks so easily because there was already a network up and running, there was already a chat room for people to meet in," said Gregg Housh, an activist who has been involved in Anonymous campaigns but disavows a personal role in any illegal online activity.

The software used to coordinate the attacks is being downloaded about 1,000 times per hour with about one-third of those downloads coming from the United States. Recently the software was improved so that a command could be sent to a supporter's computers and the attack would begin -- no human needed.

But even Mr. Barlow of the Electronic Frontier Foundation appeared to have second thoughts about where such escalation could lead: On Thursday, he said that the Anonymous group members represented "a stunning force in the world.

"But still," he said, it is "better used to open, not to close." He added that he opposed denial-of-service attacks on principle: "It's like the poison gas of cyberspace. The fundamental principle should be to open things up and not close them."

Things were hardly so serious when Anonymous first made a name for itself. The group grew out of online message boards like 4chan, an unfiltered meeting place with more than its share of misanthropic behavior and schemes.

Mr. Housh said of Anonymous: "It was deliberately not for any good. We kind of took pride in it."

That changed when Mr. Housh and a few dozen others were incensed by the Church of Scientology's attempt to use copyright law to remove a long video in which the actor Tom Cruise had spoken about church beliefs.

With its work on behalf of WikiLeaks, Anonymous has found a much more high-profile cause. As the campaign expands, many fear a more contentious Internet as governments and businesses respond to more serious attacks by activists who benefit from improvements in bandwidth and readily available hacking tools.

"Home field advantage goes to the attacker," said Gunter Ollmann, vice president of research at Damballa, an Atlanta-based firm that specializes in Internet protection. "With a little bit of coordination and growing numbers of participants, these things will continue to happen regularly."

But the coordinated attacks on major corporate and government Web sites in defense of WikiLeaks, which began on Wednesday and continued on Thursday, suggested that the loosely organized group called Anonymous might have come of age, evolving into one focused on more serious matters: in this case, their definition of Internet freedom.

While the attacks on such behemoths as MasterCard, Visa and PayPal were not nearly as sophisticated as some less publicized assaults, they were a step forward in the group's larger battle against what it sees as increasing control of the Internet by corporations and governments. This week they found a cause and an icon: Julian Assange, the former hacker who founded WikiLeaks and is now in a London jail at the request of the Swedish authorities investigating him on accusations of rape.

"This is kind of the shot heard round the world -- this is Lexington," said John Perry Barlow, a co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil liberties organization that advocates for a freer Internet.

On Thursday, the police in the Netherlands took the first official action against the campaign, detaining a 16-year-old student in his parents' home in The Hague who they said admitted to participating in attacks on MasterCard and Visa. The precise nature of his involvement was unclear, but in past investigations, the authorities have sometimes arrested those unsophisticated enough not to cover their tracks on the Web.

Meanwhile, a lawyer for Mr. Assange, 39, said he strongly denied that he had encouraged any attacks on behalf of WikiLeaks.

"It is absolutely false," the lawyer, Jennifer Robinson, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in London on Thursday. "He did not make any such instruction, and indeed he sees that as a deliberate attempt to conflate hacking organizations" with "WikiLeaks, which is not a hacking organization. It is a news organization and a publisher."

Although Anonymous remains shadowy and without public leaders, it developed a loose hierarchy in recent years as it took on groups as diverse as the Church of Scientology and the Motion Picture Association of America.

The coordination and the tactics developed in those campaigns appeared to make this week's attacks more powerful, allowing what analysts believe is a small group to enlist thousands of activists to bombard Web sites with traffic, making them at least temporarily inaccessible. Experts say the group appears to have used more sophisticated software this time that allowed supporters to repeatedly visit the sites at a specific time when the command was given.

The Twitter account identified with the Anonymous movement contained messages with little more than the words "Fire now."

The attacks thus far have been of limited effect, shutting down the MasterCard Web site, not its online transactions.

But to security experts and people who have tracked or participated in the Anonymous movement, they indicated a step forward for cyberanarchists railing against the "elites" -- corporations and governments with power over both the machinery and, critics increasingly argue, the content on the Web.

"In the past, Anonymous made quite a lot of noise but did little damage," said Amichai Shulman, chief technology officer at Imperva, a California-based security technology company. "It's different this time around. They are starting to use the same tools that industrial hackers are using."

Despite the name, Anonymous can be found in many locations and formats. Members converse in online forums and chat rooms where friendships and alliances often build.

"It's the first place I go when I turn on my computer," said one Anonymous activist, reached on an online chat service, who did not want to be named discussing the structure of the organization.

Groups of these friends, who form new conversations, or threads, sometimes decide on a topic or an issue that they feel is deserving of more attention, the activist said.

"You post things, discuss ideas and that leads to putting out a video or a document" for a campaign. In the case of WikiLeaks, the activist said, it appears that two groups decided almost simultaneously to mount a concerted effort against the site's enemies.

"I got e-mailed these two links on Sunday or Monday," he said. Denouncing "what's being done to Julian and WikiLeaks," he said, he decided to join in.

These ideas bubble up, but ultimately a small group decides exactly what affiliated site should be attacked and when, according to a Dutch writer on the Anonymous movement, who writes a blog under the name Ernesto Van der Sar. There is a chat room "that is invite only, with a dozen or so people," he said, that pick the targets and the time of attack.

He described the typical Anonymous member as young; he guessed 18 to 24 years old.

While Anonymous has recently had success with attacks on sites related to copyright infringement cases, the WikiLeaks cause has brought a much greater intensity to its efforts.

The campaigns are part of Operation Payback, created in the summer to defend a file-sharing site in Sweden that counts itself part of the mission of keeping the Internet unfettered and unfiltered and that was singled out by the authorities.

"We could move against enemies of WikiLeaks so easily because there was already a network up and running, there was already a chat room for people to meet in," said Gregg Housh, an activist who has been involved in Anonymous campaigns but disavows a personal role in any illegal online activity.

The software used to coordinate the attacks is being downloaded about 1,000 times per hour with about one-third of those downloads coming from the United States. Recently the software was improved so that a command could be sent to a supporter's computers and the attack would begin -- no human needed.

But even Mr. Barlow of the Electronic Frontier Foundation appeared to have second thoughts about where such escalation could lead: On Thursday, he said that the Anonymous group members represented "a stunning force in the world.

"But still," he said, it is "better used to open, not to close." He added that he opposed denial-of-service attacks on principle: "It's like the poison gas of cyberspace. The fundamental principle should be to open things up and not close them."

Things were hardly so serious when Anonymous first made a name for itself. The group grew out of online message boards like 4chan, an unfiltered meeting place with more than its share of misanthropic behavior and schemes.

Mr. Housh said of Anonymous: "It was deliberately not for any good. We kind of took pride in it."

That changed when Mr. Housh and a few dozen others were incensed by the Church of Scientology's attempt to use copyright law to remove a long video in which the actor Tom Cruise had spoken about church beliefs.

With its work on behalf of WikiLeaks, Anonymous has found a much more high-profile cause. As the campaign expands, many fear a more contentious Internet as governments and businesses respond to more serious attacks by activists who benefit from improvements in bandwidth and readily available hacking tools.

"Home field advantage goes to the attacker," said Gunter Ollmann, vice president of research at Damballa, an Atlanta-based firm that specializes in Internet protection. "With a little bit of coordination and growing numbers of participants, these things will continue to happen regularly."

Comments

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Popular on Gadgets

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

Latest Gadgets

- Tecno Pova Curve 2 5G

- Lava Yuva Star 3

- Honor X6d

- OPPO K14x 5G

- Samsung Galaxy F70e 5G

- iQOO 15 Ultra

- OPPO A6v 5G

- OPPO A6i+ 5G

- Asus Vivobook 16 (M1605NAQ)

- Asus Vivobook 15 (2026)

- Brave Ark 2-in-1

- Black Shark Gaming Tablet

- boAt Chrome Iris

- HMD Watch P1

- Haier H5E Series

- Acerpure Nitro Z Series 100-inch QLED TV

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)

© Copyright Red Pixels Ventures Limited 2026. All rights reserved.

![[Partner Content] OPPO Reno15 Series: AI Portrait Camera, Popout and First Compact Reno](https://www.gadgets360.com/static/mobile/images/spacer.png)