- Home

- Others

- Others News

- This Robot Follows You Around and Blasts You With Air Conditioning

This Robot Follows You Around and Blasts You With Air Conditioning

By Darryl Fears, The Washington Post | Updated: 1 July 2016 18:44 IST

Advertisement

Reinhard Radermacher has a vision: A person walks into a room hot and sweaty after exercising, and somewhere in the dark, tucked in a corner, a small robot notices and lights up. It moves forward and speaks.

"I see you're coming home from the gym," it says in a pleasant voice. "I will give you maximum cooling now."

This isn't a line ripped from the 2014 animated Disney movie Big Hero 6, in which a "personal health-care companion" called Baymax sprang to life whenever it sensed human pain. This is something happening now at the University of Maryland, as Radermacher and a team of engineers, researchers and designers race to develop RoCo - a robotic personal air conditioner capable of sensing when a person is too hot or too cold and taking action to make them more comfortable.

The big-picture aim is to one day cut the energy used to cool or heat a room, office or industrial space, regardless of whether anyone is there. RoCo, short for Roving Comforter, would follow its owners like a self-propelled vacuum cleaner and provide enough comfort to allow homes and businesses to adjust the thermostat up to four degrees.

Federal energy officials estimate that 14 percent of US energy output goes for air conditioning, heating and ventilation in buildings - much of which is wasted. That usage contributes to almost the same percentage of the nation's greenhouse-gas emissions. Saving only two degrees of energy would be "an enormous amount," equal to converting a quarter of all vehicles on the road to electric hybrids, said Jennifer Gerbi, program director for the Department of Energy's Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy.

Maryland's team is competing in a three-year challenge organized by an agency program called Delivering Efficient Local Thermal Amenities, or DELTA. It provides financial support to cutting-edge technological innovations too new or risky for private-sector investment. The competition is helping to get the ball rolling on advances that could improve national security, defense and the environment.

Three other schools are also pursuing energy-saving projects, and all have the potential of going to market, although Gerbi doesn't expect that to ultimately happen.

Syracuse University is designing a small box that would sit on a work desk or near a chair at home and perform a function similar to RoCo's. Stony Brook University at New York is working on special vents that blow cooled air on individuals. And the University of California at Berkeley is testing a chair that heats or cools its occupant, which Gerbi described as "wonderful."

"The chair heats a small part of your back, but your entire body feels warm," she said. "People are looking at very clever and novel ways of using tech."

Office battles have long been fought over room temperature, with women typically complaining of feeling frozen. The dozen or so people behind RoCo could help keep the peace.

But can they reach their goal in time? Can the Maryland team design a robot savvy enough to know when you're sweating or shivering and sell it for the current goal of $60? Gerbi said she thinks warehouse operators would love how RoCo could lower energy costs in big rooms with a handful of employees. But she's not so sure about an army of R2-D2-sized robots roaming a crowded office space.

It took time for the Maryland team to figure out its project. Engineering professors Vikrant Aute and Jiazhen Ling were part of a group that tossed ideas around for months. Some were almost laughably basic, such as a fan that would blow air over an ice bucket. Aute and Ling decided that wasn't good enough, and the Energy Department provided the university with about $2.5 million for the team to think bigger.

As the ideas became more ambitious, Radermacher and others dreamed of a robot that would not sit idly while people suffered. It would be cute, thoughtful and intuitive, knowing when its owner was in distress. Unlike the fans available at home ware stores, it would power on by itself, monitor motion, create cool air and somehow store the heat generated in the process. Signaled via wearable technology or perhaps a cellphone app, it also would adjust its height to custom-cool its user.

Daniel Dalgo is focusing on the wearable, serving as a guinea pig with sensors stuck on his bare chest to determine if his vitals can be downloaded into a secure digital cloud. "I think that's what's going to be the impact of this project," said Dalgo, a graduate research assistant. "It will allow people to be comfortable in their environment without playing with the thermostat."

"We want to see how far we can take this," said Radermacher, director of the university's Center for Environmental Energy Engineering. When RoCo comes within three feet of a user, "it will blow air maybe at your face or maybe your chest."

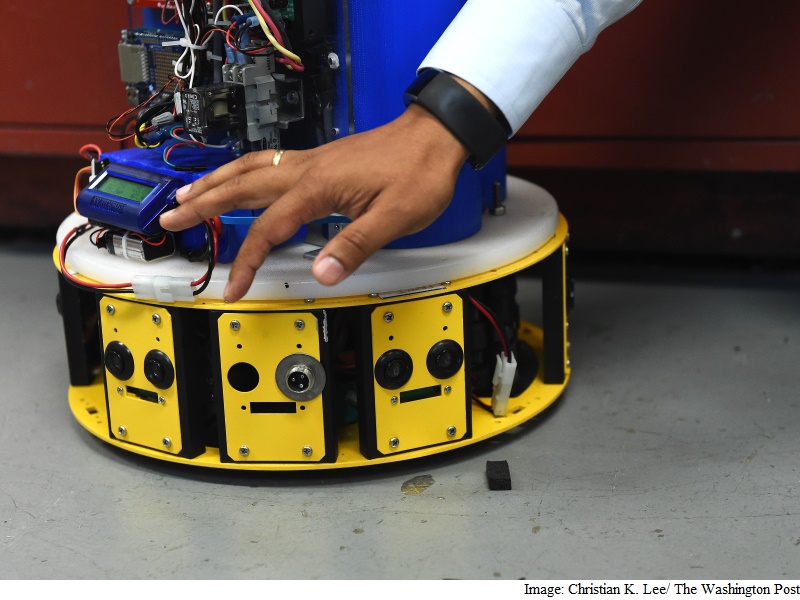

Over the past seven months, the team mounted a tiny compressor and fan on its prototype. Someone found a large nozzle on the Chinese equivalent of Amazon.com and had it shipped to the school. That piece is now the cyclops-like portal that directs the air, while three tubes are used to store and release the heat produced. A round, yellow base serves as the wheeled charging port.

The commands are delivered via the touch-screen of an Android tablet. During a recent demonstration at the engineering school, Aute merely glided his finger around a circle to make RoCo twirl.

But while functional, RoCo still needs cosmetic work. Wires appear to come and go everywhere. It doesn't yet speak or have the ability to heat a surrounding space. It moves with the whir of a remote-control race car and only operates for a max of two hours before requiring a two-hour charge.

The team has a couple more years to give it an attractive appearance and soothing voice. Two students recruited for the outer design work came up with radically different ideas: One resembles a curving steamship pipe, while the other looks like a curvy body with Jennifer Lopez-like hips.

"There's a whole lot to say about both of them," Radermacher said. "One is the more attractive one; one is more technical. They have their advantages and disadvantages."

© 2016 The Washington Post

"I see you're coming home from the gym," it says in a pleasant voice. "I will give you maximum cooling now."

This isn't a line ripped from the 2014 animated Disney movie Big Hero 6, in which a "personal health-care companion" called Baymax sprang to life whenever it sensed human pain. This is something happening now at the University of Maryland, as Radermacher and a team of engineers, researchers and designers race to develop RoCo - a robotic personal air conditioner capable of sensing when a person is too hot or too cold and taking action to make them more comfortable.

The big-picture aim is to one day cut the energy used to cool or heat a room, office or industrial space, regardless of whether anyone is there. RoCo, short for Roving Comforter, would follow its owners like a self-propelled vacuum cleaner and provide enough comfort to allow homes and businesses to adjust the thermostat up to four degrees.

Federal energy officials estimate that 14 percent of US energy output goes for air conditioning, heating and ventilation in buildings - much of which is wasted. That usage contributes to almost the same percentage of the nation's greenhouse-gas emissions. Saving only two degrees of energy would be "an enormous amount," equal to converting a quarter of all vehicles on the road to electric hybrids, said Jennifer Gerbi, program director for the Department of Energy's Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy.

Maryland's team is competing in a three-year challenge organized by an agency program called Delivering Efficient Local Thermal Amenities, or DELTA. It provides financial support to cutting-edge technological innovations too new or risky for private-sector investment. The competition is helping to get the ball rolling on advances that could improve national security, defense and the environment.

Three other schools are also pursuing energy-saving projects, and all have the potential of going to market, although Gerbi doesn't expect that to ultimately happen.

Syracuse University is designing a small box that would sit on a work desk or near a chair at home and perform a function similar to RoCo's. Stony Brook University at New York is working on special vents that blow cooled air on individuals. And the University of California at Berkeley is testing a chair that heats or cools its occupant, which Gerbi described as "wonderful."

"The chair heats a small part of your back, but your entire body feels warm," she said. "People are looking at very clever and novel ways of using tech."

Office battles have long been fought over room temperature, with women typically complaining of feeling frozen. The dozen or so people behind RoCo could help keep the peace.

But can they reach their goal in time? Can the Maryland team design a robot savvy enough to know when you're sweating or shivering and sell it for the current goal of $60? Gerbi said she thinks warehouse operators would love how RoCo could lower energy costs in big rooms with a handful of employees. But she's not so sure about an army of R2-D2-sized robots roaming a crowded office space.

It took time for the Maryland team to figure out its project. Engineering professors Vikrant Aute and Jiazhen Ling were part of a group that tossed ideas around for months. Some were almost laughably basic, such as a fan that would blow air over an ice bucket. Aute and Ling decided that wasn't good enough, and the Energy Department provided the university with about $2.5 million for the team to think bigger.

As the ideas became more ambitious, Radermacher and others dreamed of a robot that would not sit idly while people suffered. It would be cute, thoughtful and intuitive, knowing when its owner was in distress. Unlike the fans available at home ware stores, it would power on by itself, monitor motion, create cool air and somehow store the heat generated in the process. Signaled via wearable technology or perhaps a cellphone app, it also would adjust its height to custom-cool its user.

Daniel Dalgo is focusing on the wearable, serving as a guinea pig with sensors stuck on his bare chest to determine if his vitals can be downloaded into a secure digital cloud. "I think that's what's going to be the impact of this project," said Dalgo, a graduate research assistant. "It will allow people to be comfortable in their environment without playing with the thermostat."

"We want to see how far we can take this," said Radermacher, director of the university's Center for Environmental Energy Engineering. When RoCo comes within three feet of a user, "it will blow air maybe at your face or maybe your chest."

Over the past seven months, the team mounted a tiny compressor and fan on its prototype. Someone found a large nozzle on the Chinese equivalent of Amazon.com and had it shipped to the school. That piece is now the cyclops-like portal that directs the air, while three tubes are used to store and release the heat produced. A round, yellow base serves as the wheeled charging port.

The commands are delivered via the touch-screen of an Android tablet. During a recent demonstration at the engineering school, Aute merely glided his finger around a circle to make RoCo twirl.

But while functional, RoCo still needs cosmetic work. Wires appear to come and go everywhere. It doesn't yet speak or have the ability to heat a surrounding space. It moves with the whir of a remote-control race car and only operates for a max of two hours before requiring a two-hour charge.

The team has a couple more years to give it an attractive appearance and soothing voice. Two students recruited for the outer design work came up with radically different ideas: One resembles a curving steamship pipe, while the other looks like a curvy body with Jennifer Lopez-like hips.

"There's a whole lot to say about both of them," Radermacher said. "One is the more attractive one; one is more technical. They have their advantages and disadvantages."

© 2016 The Washington Post

Comments

For the latest tech news and reviews, follow Gadgets 360 on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News. For the latest videos on gadgets and tech, subscribe to our YouTube channel. If you want to know everything about top influencers, follow our in-house Who'sThat360 on Instagram and YouTube.

Popular on Gadgets

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025

- ChatGPT

- Redmi Note 14 Pro+

- iPhone 16

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

Latest Gadgets

- Motorola Edge 60

- Motorola Edge 60 Pro

- Motorola Razr 60

- Motorola Razr 60 Ultra

- Realme 14T 5G

- Redmi Turbo 4 Pro

- Honor X70i

- Red Magic 10 Air

- HP EliteBook 6 G1a

- HP EliteBook 8 G1a

- Honor Pad GT

- Vivo Pad SE

- Moto Watch Fit

- Honor Band 10

- Xiaomi X Pro QLED 2025 (43-Inch)

- Xiaomi X Pro QLED 2025 (55-Inch)

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Toshiba 1.8 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (RAS-24TKCV5G-INZ / RAS-24TACV5G-INZ)

- Toshiba 1.5 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (RAS-18PKCV2G-IN / RAS-18PACV2G-IN)

© Copyright Red Pixels Ventures Limited 2025. All rights reserved.