- Home

- Others

- Others News

- Steve Jobs' bio talks of wild mood swings of a genius at work

Steve Jobs' bio talks of wild mood swings of a genius at work

By Associated Press | Updated: 6 June 2012 15:17 IST

Advertisement

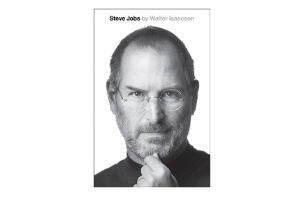

Walter Isaacson's "Steve Jobs" takes off the rose-colored glasses that often follow an icon's untimely death and instead offers something far more valuable: The chronicle of a complex, brash genius who was crazy enough to think he could change the world - and did.

Through unprecedented access to Jobs with more than 40 conversations, including long sessions sitting in the Apple co-founder's living room, walks around his childhood neighborhood and visits to his company's secretive headquarters, Isaacson takes the reader on a journey that few have had the opportunity to experience.

The book is the first, and with his Oct. 5 death at age 56, the only authorized biography of the famously private Jobs and by extension, the equally secretive Apple Inc. Through Apple, Jobs helped usher in the personal computer era when he put the Macintosh in the hands of regular people. He changed the course of the music, computer animation and mobile phone industries, and touched countless others with the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad, Pixar and iTunes.

His biography, therefore, serves as a chronicle of Silicon Valley, of late 20th- and early 21st-century technology, and of American innovation at its best. For the generation that's grown up in a world where computers are the norm, smartphones feel like fifth limbs and music comes from the Internet rather than record and CD stores, "Steve Jobs" is must-read history.

Isaacson, whose other books include biographies of Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin and Henry Kissinger, uses anecdotes from friends, family, colleagues and adversaries to illustrate sometimes deep contradictions in Jobs.

Given up for adoption at birth, the young Jobs would go on to deny his daughter Lisa for years. The product of 1960s counterculture who shunned materialism, he'd go on to found what would become the world's most valuable company. Deeply influenced by the tenets of Zen Buddhism, Jobs rarely achieved the internal peace associated with it and was prone to wild mood swings and mean outbursts at people who weren't living up to his expectations.

But it's these contradictions that make the out-of-this-world Apple magician human to a fault. And it's his uncanny ability to meld art and technology, design and engineering, beauty and function that allowed him to put the Macintosh, the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad into the hands of millions of people who didn't even know they wanted them. Jobs changed our relationship with technology because he understood humanity as well as he understood chips and interfaces.

"I'm one of the few people who understands how producing technology requires intuition and creativity, and how producing something artistic takes real discipline," Jobs tells Isaacson in one of the extended passages in the book that are in his own words.

These longer interview excerpts pepper the book like rare gems. In them, Jobs offers eloquent, no-apologies explanations of why he did things the way he did and what was going on in his mind amid decisions at Apple and in his own life.

Apple fanboys, tech geeks and encyclopedic-minded journalists will likely comb the book for previously unknown details about Jobs and Apple. I went into it with only a little more knowledge than the average reader, and a tenuous, nostalgic connection to him through having attended high school with his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs. I found myself combing the book not for secrets about Apple, but secrets about Steve Jobs the man, the father, the son.

With little patience for technical details, I found myself skimming through some of the book's passages detailing the creation of the Apple I computer, the Macintosh and the i-gadgets of Jobs' later years. It's in these passages, though, where the reader might find explanations for why the iPhone's battery is not replaceable, why Macs cost more than PCs and why the iPod's headphones are white.

The intimate chapters, where Jobs' personal side shines through, with all his faults and craziness, leave a deep impression. There's humor, too, especially early on when Isaacson chronicles Jobs' lack of personal hygiene, the barefoot hippie who runs a corporation. And deeply moving are passages about Jobs' resignation as Apple's chief executive, and an afternoon he spent with Isaacson listening to music and reminiscing.

"Steve Jobs" was originally scheduled to hit store shelves in 2012. Its publication date was moved up after Jobs died. As such, there are bits that might have benefited from another round of editing. There are anecdotes, for example, that Isaacson repeats as if introducing them to the reader for the first time.

In the end, it's a rich portrait of one of the greatest minds of our generation.

Through unprecedented access to Jobs with more than 40 conversations, including long sessions sitting in the Apple co-founder's living room, walks around his childhood neighborhood and visits to his company's secretive headquarters, Isaacson takes the reader on a journey that few have had the opportunity to experience.

The book is the first, and with his Oct. 5 death at age 56, the only authorized biography of the famously private Jobs and by extension, the equally secretive Apple Inc. Through Apple, Jobs helped usher in the personal computer era when he put the Macintosh in the hands of regular people. He changed the course of the music, computer animation and mobile phone industries, and touched countless others with the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad, Pixar and iTunes.

His biography, therefore, serves as a chronicle of Silicon Valley, of late 20th- and early 21st-century technology, and of American innovation at its best. For the generation that's grown up in a world where computers are the norm, smartphones feel like fifth limbs and music comes from the Internet rather than record and CD stores, "Steve Jobs" is must-read history.

Isaacson, whose other books include biographies of Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin and Henry Kissinger, uses anecdotes from friends, family, colleagues and adversaries to illustrate sometimes deep contradictions in Jobs.

Given up for adoption at birth, the young Jobs would go on to deny his daughter Lisa for years. The product of 1960s counterculture who shunned materialism, he'd go on to found what would become the world's most valuable company. Deeply influenced by the tenets of Zen Buddhism, Jobs rarely achieved the internal peace associated with it and was prone to wild mood swings and mean outbursts at people who weren't living up to his expectations.

But it's these contradictions that make the out-of-this-world Apple magician human to a fault. And it's his uncanny ability to meld art and technology, design and engineering, beauty and function that allowed him to put the Macintosh, the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad into the hands of millions of people who didn't even know they wanted them. Jobs changed our relationship with technology because he understood humanity as well as he understood chips and interfaces.

"I'm one of the few people who understands how producing technology requires intuition and creativity, and how producing something artistic takes real discipline," Jobs tells Isaacson in one of the extended passages in the book that are in his own words.

These longer interview excerpts pepper the book like rare gems. In them, Jobs offers eloquent, no-apologies explanations of why he did things the way he did and what was going on in his mind amid decisions at Apple and in his own life.

Apple fanboys, tech geeks and encyclopedic-minded journalists will likely comb the book for previously unknown details about Jobs and Apple. I went into it with only a little more knowledge than the average reader, and a tenuous, nostalgic connection to him through having attended high school with his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs. I found myself combing the book not for secrets about Apple, but secrets about Steve Jobs the man, the father, the son.

With little patience for technical details, I found myself skimming through some of the book's passages detailing the creation of the Apple I computer, the Macintosh and the i-gadgets of Jobs' later years. It's in these passages, though, where the reader might find explanations for why the iPhone's battery is not replaceable, why Macs cost more than PCs and why the iPod's headphones are white.

The intimate chapters, where Jobs' personal side shines through, with all his faults and craziness, leave a deep impression. There's humor, too, especially early on when Isaacson chronicles Jobs' lack of personal hygiene, the barefoot hippie who runs a corporation. And deeply moving are passages about Jobs' resignation as Apple's chief executive, and an afternoon he spent with Isaacson listening to music and reminiscing.

"Steve Jobs" was originally scheduled to hit store shelves in 2012. Its publication date was moved up after Jobs died. As such, there are bits that might have benefited from another round of editing. There are anecdotes, for example, that Isaacson repeats as if introducing them to the reader for the first time.

In the end, it's a rich portrait of one of the greatest minds of our generation.

Comments

Catch the latest from the Consumer Electronics Show on Gadgets 360, at our CES 2025 hub.

Popular on Gadgets

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025

- ChatGPT

- Redmi Note 14 Pro+

- iPhone 16

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

Latest Gadgets

- Poco X7 Pro 5G

- Poco X7 5G

- Nubia Music 2

- OnePlus 13R

- Moto G05

- Oppo Reno 13F 4G

- Oppo Reno 13F 5G

- Huawei Nova 13i

- Lenovo Yoga Slim 9i (2025)

- Lenovo ThinkPad X9 15 Aura Edition

- Honor Pad X9 Pro

- Honor Pad V9

- Amazfit Active 2

- boAt Enigma Gem

- Sony 65 Inches Ultra HD (4K) LED Smart TV (KD-65X74L)

- TCL 55 Inches Ultra HD (4K) LED Smart TV (55C61B)

- Sony PlayStation 5 Pro

- Sony PlayStation 5 Slim Digital Edition

- Blue Star 1.5 Ton 3 Star Inverter Split AC (IC318DNUHC)

- Blue Star 1.5 Ton 3 Star Inverter Split AC (IA318VKU)

© Copyright Red Pixels Ventures Limited 2025. All rights reserved.