- Home

- Others

- Others News

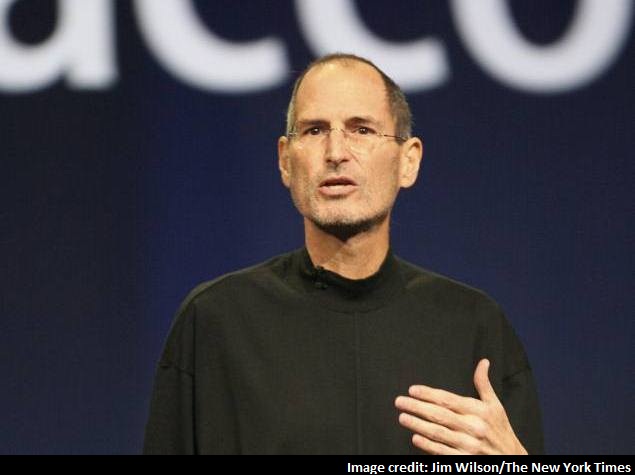

- Steve Jobs, a Genius at Pushing Boundaries

Steve Jobs, a Genius at Pushing Boundaries

That's the provocative question being debated in antitrust circles in the wake of revelations that Jobs, the co-founder of Apple who is deeply revered in Silicon Valley, was the driving force in a conspiracy to prevent competitors from poaching employees. Jobs seems never to have read, or may have chosen to ignore, the first paragraph of the Sherman Antitrust Act:

Every "conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce" is illegal, the act says. "Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine" or "by imprisonment not exceeding three years, or by both said punishments."

Jobs "was a walking antitrust violation," said Herbert Hovenkamp, a professor at the University of Iowa College of Law and an expert in antitrust law. "I'm simply astounded by the risks he seemed willing to take."

The anti-poaching pact was hardly Jobs' only post-mortem brush with the law. His behavior was at the center of an e-book price-fixing conspiracy with major publishers. After a lengthy trial, a federal judge ruled last summer that "Apple played a central role in facilitating and executing that conspiracy." (Apple has appealed the decision. The publishers all settled the case.)

(Also see: Steve Jobs evidence in focus ahead of next month's 'no poaching' trial)

Jobs also figured prominently in the options backdating scandal that rocked Silicon Valley eight years ago. Thousands of options were backdated at both Apple and computer animation studio Pixar, where Jobs was also chief executive, to increase the value of option grants to senior employees. An investigation by Apple's lawyers cleared Jobs of wrongdoing, saying he didn't understand the accounting implications. But it concluded that he "was aware or recommended the selection of some favorable grant dates." Jobs himself received options on 7.5 million shares, which were backdated to immediately bolster their value by more than $20 million. Apple admitted that the minutes of the October board meeting where the grant was supposedly approved were fabricated, that no such meeting had occurred and that the options were actually granted in December.

Five executives of other companies went to prison for backdating options, but Jobs was never charged. (Other Apple executives eventually settled Securities and Exchange Commission charges and left the company. The commission did praise Apple itself for its "swift, extensive and extraordinary cooperation.")

Despite the strict language of the Sherman Act, the Justice Department tends to file criminal antitrust charges only in the most egregious cases, and by that standard, Jobs would probably never have been charged. Still, Jobs' conduct is a reminder that the difference between genius and potentially criminal behavior can be a fine line. Jobs "always believed that the rules that applied to ordinary people didn't apply to him," Walter Isaacson, author of the best-selling biography "Steve Jobs," told me this week. "That was Steve's genius but also his oddness. He believed he could bend the laws of physics and distort reality. That allowed him to do some amazing things, but also led him to push the envelope."

Hovenkamp characterized both the e-book agreements and the anti-poaching pact as "blatant restraints of trade." Jobs, he said, "was so casual about it, so bold. Didn't he have lawyers advising him? You see this kind of behavior sometimes in small, private or family-run companies, but almost never in large public companies like Apple."

Apple declined to comment.Jobs was certainly brazen. Testimony in the e-books case suggested that Jobs was eager, even frantic, to have an e-book agreement in place in time for his announcement of Apple's latest product, the iPad. There's no indication that any lawyers put the brakes on. (On the contrary, the chief architect of the scheme inside Apple was a lawyer.) In an email to James Murdoch, then an executive at News Corp., which owned publisher HarperCollins, Jobs offered what amounted to a case in price fixing: "Our proposal does set the upper limit for e-book retail pricing based on the hardcover price of each book" and urged HarperCollins to "throw in with Apple."

HarperCollins did, along with other major publishers. Judge Denise L. Cote of U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled that "Apple is liable here for facilitating and encouraging the publisher defendants' collective, illegal restraint of trade," adding: "Through their conspiracy, they forced Amazon (and other resellers) to relinquish retail pricing authority and then they raised retail e-book prices. Those higher prices were not the result of regular market forces but of a scheme in which Apple was a full participant."

(Also see: Keep Jobs' personality out of anti-poaching trial: Tech firms)

Why were no criminal charges filed? The Justice Department's antitrust division chief, William J. Baer, recently noted that the department had filed 339 criminal antitrust cases since President Barack Obama took office, many of them on charges of price-fixing. The issue is, of course, moot with Jobs, who died in 2011. But his co-conspirators in the publishing industry may have benefited from the relative novelty of e-books. "There's a traditional reluctance to go for criminal liability over novel practices," Hovenkamp said. "There was probably some thinking that with e-books, the technology was so new, and it was disruptive. It's tough to prove mens rea," or criminal state of mind.

And there may have been political constraints, too. Although consumers were the beneficiaries of the case (and prices of e-books have dropped since the case was settled), publishers and their allies, including many authors, warned that the perverse result was to solidify Amazon's dominance.

The anti-poaching case may be taking a bigger toll on Jobs' reputation, especially since he seemed so cavalier about people's jobs. Jobs was again injudicious in his emails to competitors. In 2007, he threatened Palm Inc. with patent litigation unless Palm agreed not to recruit Apple employees, even though Palm's then-chief executive, Edward Colligan, told him that such a plan was "likely illegal."

That same year, Jobs wrote Eric E. Schmidt, chief executive of Google at the time, "I would be extremely pleased if Google would stop doing this," referring to its efforts to recruit an Apple engineer. Schmidt forwarded the email, adding his own indiscreet comment: "I believe we have a policy of no recruiting from Apple and this is a direct inbound request. Can you get this stopped and let me know why this is happening? I will need to send a response back to Apple quickly so please let me know as soon as you can."

When Jobs learned that the Google recruiter who contacted the Apple employee would be "fired within the hour" he responded with a smiley face.

"How could anyone have approved that?" Hovenkamp asked. "Any competent antitrust counsel would know that's illegal. And they had to know they'd get caught eventually."

Apple, Google and other technology companies reached an agreement with the Justice Department over the no-poaching practice in 2010, and agreed not to engage in any agreement or activity to reduce or prevent competition for employees. Last week, Apple and other technology companies settled a related class-action lawsuit, agreeing to pay $324 million.

Again, the Justice Department chose not to bring criminal charges against some of Silicon Valley's most prominent executives. (The Justice Department said it did not comment on decisions not to file charges.)

Both the e-book and anti-poaching cases "look suspiciously like a lot of other cases that resulted in criminal charges," Hovenkamp said. "But there's always the factor of prosecutorial discretion."

There's no way of knowing whether Jobs, had he lived and been healthy, would have faced charges, especially since he was a recidivist. Given Jobs' immense popularity, prosecutors might not have wanted to risk a trial, Hovenkamp noted. Jobs probably came closest to being prosecuted in the backdating scandal, but by then he was known to have pancreatic cancer.

But why would Jobs even have tried to skirt the law, given how much was at stake? Isaacson said he couldn't comment on specific cases, but noted that "over and over, people referred to his reality distortion field." Isaacson added, "The rules just didn't apply to him, whether he was getting a license plate that let him use handicapped parking or building products that people said weren't possible. Most of the time he was right, and he got away with it."

Brian Lam, a technology reporter and founder of The Wirecutter website, said Jobs' seeming indifference to the law wasn't unusual in Silicon Valley, and hadn't blemished Jobs' reputation there. "Look at Bill Gates," he said. "He was arrested for speeding and driving without a license. And Microsoft had its problems with antitrust law. It's just a characteristic of young tech entrepreneurs to look at the rules and question them. You can't get into this game without a healthy distaste for the status quo."

But even as Jobs was doing his best to snuff out competition, he publicly reveled in it, Isaacson said. "The paradox is, Steve Jobs was totally energized by competition. His famous 1984 ad was about destroying IBM. He later felt the same about Microsoft Windows and did the PC versus Mac ads. And in his last few years, he was obsessed with Google Android. Yes, he tried to block them in court with lawsuits. But also he competed by getting totally energized and whipping his troops into a frenzy to build better products - and announcing that all of his competitors' products sucked."For details of the latest launches and news from Samsung, Xiaomi, Realme, OnePlus, Oppo and other companies at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, visit our MWC 2026 hub.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Apple iPhone 17e

- AI+ Pulse 2

- Motorola Razr Fold

- Honor Magic V6

- Leica Leitzphone

- Samsung Galaxy S26+

- Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra

- Samsung Galaxy S26

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Pro, 2026)

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Amazfit Active 3 Premium

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)