- Home

- Others

- Others News

- Medicine that monitors you

Medicine that monitors you

As society struggles with the privacy implications of wearable computers like Google Glass, scientists, researchers and some startups are already preparing the next, even more intrusive wave of computing: ingestible computers and minuscule sensors stuffed inside pills.

Although these tiny devices are not yet mainstream, some people on the cutting edge are already swallowing them to monitor a range of health data and wirelessly share this information with a doctor. And there are prototypes of tiny, ingestible devices that can do things like automatically open car doors or fill in passwords.

For people in extreme professions, like space travel, various versions of these pills have been used for some time. But in the next year, your family physician - at least if he is technologically savvy - could also have them in his medicinal tool kit.

Inside these pills are tiny sensors and transmitters. You swallow them with water, or milk if you'd prefer. After that, the devices make their way to the stomach and stay intact as they travel through the intestinal tract.

"You will - voluntarily, I might add - take a pill, which you think of as a pill but is in fact a microscopic robot, which will monitor your systems" and wirelessly transmit what is happening, Eric E. Schmidt, the executive chairman of Google, said last fall at a company conference. "If it makes the difference between health and death, you're going to want this thing."

One of the pills, made by Proteus Digital Health, a small company in Redwood City, Calif., does not need a battery. Instead, the body is the power source. Just as a potato can power a light bulb, Proteus has added magnesium and copper on each side of its tiny sensor, which generates just enough electricity from stomach acids.

As a Proteus pill hits the bottom of the stomach, it sends information to a cellphone app through a patch worn on the body. The tiny computer can track medication-taking behaviors - "did Grandma take her pills today, and what time?" - and monitor how a patient's body is responding to medicine. It also detects the person's movements and rest patterns.

Executives at the company, which recently raised $62.5 million from investors, say they believe that these pills will help patients with physical and neurological problems. People with heart failure-related difficulties could monitor blood flow and body temperature; those with central nervous system issues, including schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease, could take the pills to monitor vital signs in real time. The Food and Drug Administration approved the Proteus pill last year.

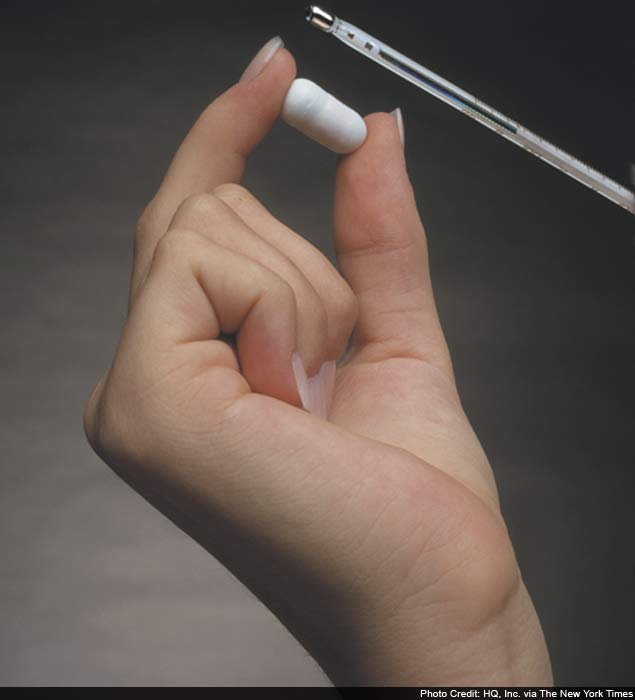

A pill called the CorTemp Ingestible Core Body Temperature Sensor, made by HQ Inc. in Palmetto, Fla., has a built-in battery and wirelessly transmits real-time body temperature as it travels through a person.

Firefighters, football players, soldiers and astronauts have used the device so their employers can monitor them and ensure they do not overheat in high temperatures. CorTemp began in 2006 as a research collaboration from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Lee Carbonelli, HQ's marketing director, said the company hoped, in the next year, to have a consumer version that would wirelessly communicate to a smartphone app.

Future generations of these pills could even be convenience tools.

Last month, Regina Dugan, senior vice president for Motorola Mobility's advanced technology and projects group, showed off an example, along with wearable radio frequency identification tattoos that attach to the skin like a sticker, at the D: All Things Digital technology conference.

Once that pill is in your body, you could pick up your smartphone and not have to type in a password. Instead, you are the password. Sit in the car and it will start. Touch the handle to your home door and it will automatically unlock. "Essentially, your entire body becomes your authentication token," Dugan said.

But if people are worried about the privacy implications of wearable computing devices, just wait until they try to wrap their heads around ingestible computing.

"This is yet another one of these technologies where there are wonderful options and terrible options, simultaneously," said John Perry Barlow, a founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a privacy advocacy group. "The wonderful is that there are a great number of things you want to know about yourself on a continual basis, especially if you're diabetic or suffer from another disease. The terrible is that health insurance companies could know about the inner workings of your body."

And the implications of a tiny computer inside your body being hacked? Let's say they are troubling.

There is, of course, one last question for this little pill. After it has done its job, flowing down around the stomach and through the intestinal tract, what happens next?

"It passes naturally thought the body in about 24 hours," Carbonelli said, but since each pill costs $46, "some people choose to recover and recycle it."

© 2013, The New York Times News Service

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Tecno Pova Curve 2 5G

- Lava Yuva Star 3

- Honor X6d

- OPPO K14x 5G

- Samsung Galaxy F70e 5G

- iQOO 15 Ultra

- OPPO A6v 5G

- OPPO A6i+ 5G

- Asus Vivobook 16 (M1605NAQ)

- Asus Vivobook 15 (2026)

- Brave Ark 2-in-1

- Black Shark Gaming Tablet

- boAt Chrome Iris

- HMD Watch P1

- Haier H5E Series

- Acerpure Nitro Z Series 100-inch QLED TV

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)

![[Partner Content] OPPO Reno15 Series: AI Portrait Camera, Popout and First Compact Reno](https://www.gadgets360.com/static/mobile/images/spacer.png)