- Home

- Mobiles

- Mobiles Features

- Apple Waves the Civil Liberties Flag, but for How Long?

Apple Waves the Civil Liberties Flag, but for How Long?

Here's a quiz I often give my business and engineering graduate students: If a website limits the topics that can be discussed, or decides who is allowed to post, or even censors comments it doesn't like, has it violated the First Amendment?

The answer is no. But it's a trick question. Tech companies can't violate the First Amendment, no matter what they do. Your freedom of speech, with limited exceptions, is only a freedom from interference by the government. You may have a hard time believing it (my students often do), but the First Amendment, along with the other protections in the Bill of Rights, does not apply to private companies, co-workers or your obnoxious brother-in-law.

That's an important feature in the escalating fight between Apple and the FBI over the contents of an iPhone used by the San Bernardino terrorists. And from the scrum of press coverage I've read, it's an aspect that few commentators understand.

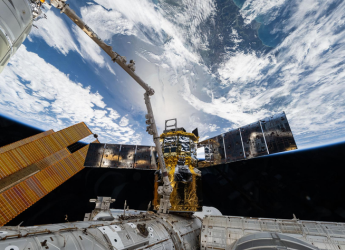

As a reminder, Apple is strenuously resisting demands to help the FBI gain access to whatever data may be on the device. In recent updates to the iPhone's operating system, the company has intentionally added features that permanently lock the device's encrypted files if anyone enters too many incorrect passcodes. The FBI got a judge to order Apple to write software to get around that feature, an order Apple is refusing to obey.

At an event Monday announcing new iPhone models, Apple chief executive Tim Cook stressed what he sees as Apple's duty to its customers. "We did not expect to be in this position, at odds with our own government, but we believe strongly we have a responsibility to help you protect your data and your privacy," he said. "We will not shrink from this responsibility."

Encrypting the data on the iPhone and limiting password attempts, of course, are among the design changes Apple has made in recent years in response to growing consumer concerns over the security of their ever-deeper digital footprints. Leading tech companies have taken similar steps to improve their hardware and software.

The emphasis on cybersecurity follows increased attacks and growing sophistication of cyber-criminals and other hackers. But the increased reliance on strong encryption technologies also comes in response to consumer fears of government snooping.

That suspicion has been part of the American psyche since the Revolutionary War, reflected in all our founding documents. In addition to the First Amendment, for example, much of the Bill of Rights can be seen as a set of constraints against the government's circumscribing, monitoring, collecting, or using personal information.

(Europeans, it is worth noting, have a much more limited view of free speech, one formed in response to a series of information-related catastrophes including the Inquisition, the Holocaust and Soviet police states. As Internet pioneer John Perry Barlow famously said, "In cyberspace the First Amendment is a local ordinance.")

Americans value their civil liberties, but they also want effective law enforcement. Fights over enhanced technologies for privacy (e.g., encryption) on the one hand and intelligence-gathering (e.g., electronic surveillance) on the other are just the latest in an arms race that has lasted over 200 years. The goal is always to maintain a delicate balance between privacy and security.

In its fight with the FBI, Apple is aggressively promoting itself as the guardian of its users' constitutional rights. That may well be, but it's no coincidence that doing so gives the company a competitive advantage over rivals such as Google, Facebook and Yahoo, whose business models rely on free or subsidized services paid for by targeted advertising and other data mining. Or, as Cook put it, "by lulling their customers into complacency about their personal information."

Whatever its motives, Apple has engineered ways to make it harder to cooperate with governments because the company believes that's what its customers want, and are willing to pay premium prices to get.

But the privacy/security pendulum is always in motion. If Apple perceives a change in public sentiment, perhaps in response to future horrific acts, there's no law that keeps them from changing with it.

Business considerations aside, Apple is under absolutely no obligation to continue encrypting its users' data or making it harder for third parties to access. The company could change its mind at any time, or offer the government all the help it wants, without Apple violating anyone's civil liberties. Its actions either way are entirely voluntary.

Which may speak to a bigger problem for technology users. As more and more of our public life moves from town squares to cloud servers, Internet companies increasingly run the governments of our virtual selves. The digital constitution takes the form of Internet protocols developed by the engineers; Internet laws are the terms and conditions of contracts between product developers and their customers.

And where physical governments are constrained by the Constitution, the only thing that limits these private lawmakers are the market forces that determine which products we buy or which services we use. The law of the Internet can change as fast as a new terms of service agreement. Your choice is simply to continue using the technology or not.

Consider the social news site Reddit, which last year announced a confusing set of changes to its code of conduct in a clumsy effort to curb behavior that some users found offensive. Several forums dominated by sexist or otherwise offensive posts were simply erased. The deleted groups, said short-lived CEO Ellen Pao, "break our reddit rules based on their harassment of individuals," a determination made solely by the company. (Due process is also a government-only requirement.)

After users and volunteer editors revolted over both the policy change and its ham-fisted implementation, Reddit's board of directors dismissed Pao and revised yet again the amendments to its speech code. But Reddit founder and returning CEO Steve Huffman still defended the changes, reminding users that the company was under no obligation to operate its free forum as if it were the U.S. government. Neither he nor his co-founder Alexis Ohanian, Huffman said, had "created reddit to be a bastion of free speech, but rather as a place where open and honest discussion can happen."

Except that Ohanian, in an interview a few years earlier, had said precisely the opposite, down to the same archaic phrasing. When Forbes reporter Kashmir Hill asked him what he thought the founding fathers would have made of the site's unregulated free-for-all of opinions, Ohanian replied, "A bastion of free speech on the World Wide Web? I bet they would like it."

If websites, device makers and other digital enterprises can rewrite both their rules and their history at will, then don't we need a different approach to Internet governance? Shouldn't user demand enforceable legal protections to ensure our civil liberties travel with us when we cross over from environments administered by physical governments to those ruled by engineers?

The answer is no, and the reason is the same one that led to the adoption of the Bill of Rights in the first place. Freedom of speech is premised on the Enlightenment belief that keeping government out of the information business created an unregulated marketplace of ideas, where good speech would ultimately win out over bad, and where informed citizens could decide whose arguments they believed and act accordingly. Governments can't put their thumb on the scale either way, even with the best intentions.

The founding fathers understood the terrible temptation for elected officials in times of crisis to take short-term actions that undermine fundamental rights. When it comes to the kind of speech that might change minds or put defendants in jail, governments can't be trusted with control of the microphone.

But nor can they be trusted to legislate the same restriction against private actors. If lawmakers could force private companies to respect the civil rights of their customers, the same lawmakers could just as easily pass laws undoing those protections, or warp them to fit the short-term needs of law enforcement, foreign policy, partisan politics, or the local mosquito abatement district.

As the Supreme Court recently underscored in a case that rejected California's mandatory age restrictions for violent video games, the First Amendment ensures not only that the government doesn't impose undue limits on speech, but also that it doesn't deputize private actors to do the job for them.

For over 200 years, the marketplace of ideas has functioned exceptionally well, regardless of the technology being used - printing press, radio and television, telegraph and telephone, and now the Internet. Every day, 2.5 quintillion bytes of new content is created by billions of users worldwide. That's a lot of free speech - and much of it available, well, for free.

What is true is that as our digital lives become richer and more connected, challenges to the unique form of digital law created by the engineers, entrepreneurs, investors and users will get messier and more contentious. But at least so far, new technologies have both created and then solved Internet governance problems with remarkable efficiency.

Today's corporate civil libertarian may turn out to be tomorrow's totalitarian heel. But innovators will continue to find ways to correct behavior that consumers don't like. Our virtual selves vote with our clicks for businesses who share our values.

The Internet is hardly a utopia. But then, neither is the world we live in the rest of the time.

© 2016 The Washington Post

For details of the latest launches and news from Samsung, Xiaomi, Realme, OnePlus, Oppo and other companies at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, visit our MWC 2026 hub.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Nothing Phone 4a Pro

- Infinix Note 60 Ultra

- Nothing Phone 4a

- Honor 600 Lite

- Nubia Neo 5 GT

- Realme Narzo Power 5G

- Vivo X300 FE

- Tecno Pop X

- MacBook Neo

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- Tecno Megapad 2

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Tecno Watch GT 1S

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)