- Home

- Laptops

- Laptops Reviews

- Intel Optane Memory Review

Intel Optane Memory Review

Intel first announced its 3D Xpoint memory technology over two years ago. Developed jointly with Micron, this new kind of non-volatile chip was supposed to be as fast as RAM and as inexpensive as SSDs. The companies described it as revolutionary, and indeed, such a thing would change one of the most fundamental constants of PC architecture as we know it today - unifying RAM and storage into a single fast, non-volatile pool. Intel then introduced the Optane brand for 3D Xpoint products, but things have been a little muted after that. Products were supposed to have launched in 2016, but we're more than halfway through 2017 and Optane hasn't yet made its mark.

The first shipping product, Intel's Optane SSD DC 4800X, gave the world a little taste of that possibility earlier this year. However, it was limited in scope and capacity, and also rather expensive. Intel downplayed the launch and pitched it only at the machine learning and big data analytics markets. Fast-forward a little bit and we finally have the first widely available consumer Optane product.

Optane Memory comes in the form of M.2 modules, using the same form factor as many of today's high-end SSDs. It's available in 16GB and 32GB versions that plug right into the slots on existing motherboards. Compatibility is restricted to Intel's 7th Generation Core processors and 2xx-series motherboards (now including the new high-end Core X-series).

Despite looking like SSDs, these are completely different devices and the pitch to consumers is also very different. These products also focus on the lowest end of the market, where slow mechanical hard drives are still standard. We're eager to see how much of a revolution Optane truly is.

![]()

What is Optane and who is it for?

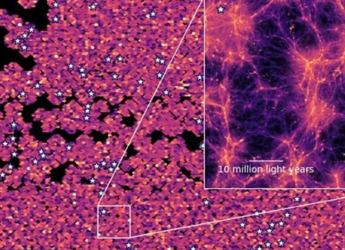

PCs have a hierarchy of memory locations, starting with the CPU's embedded caches and moving outwards to RAM and then to fixed and external storage devices. As you go outwards, latency and capacity increase and cost goes down. A CPU's effectiveness depends on how well it can keep important data and instructions close at hand. It would waste several cycles to fetch and deliver them from RAM, and far more to traverse through the motherboard's various subsystems to get to a hard drive, which itself is nowhere near as fast as flash storage.

That's one of the key reasons that increasing the amount of RAM in a PC improves performance so much. It's also why SSDs in general (and PCIe SSDs in particular) are much faster than spinning hard drives. Unfortunately, both RAM and SSDs are the first to be cut down when anyone is trying to manage costs.

What Intel is saying now is that an Optane Memory module can sit between the RAM and storage, acting as a small but very fast buffer. It's targeted at PCs with spinning hard drives, since SSDs are fast enough by nature. This is essentially an extension of the hybrid "SSHD" drives we've seen before which have a little flash memory grafted onto a hard drive, or implementations like Apple's Fusion Drive. In fact, Intel itself did something very similar with its Smart Response caching technology for the Sandy Bridge generation of CPUs in 2011, long before SSDs were affordable enough for the mainstream market.

3D Xpoint (pronounced "crosspoint") is interesting because the new structure that Intel and Micron have developed has different performance characteristics than the standard NAND flash used in SSDs such as much lower latency. According to both Intel and Micron at the time of its unveiling, 3D Xpoint can be 1000x faster and 1000x more reliable than ordinary NAND flash. It's also physically smaller, allowing for greater data density. Interestingly, Micron will be bringing the same technology to market under its own brand, QuantX, but not until another generation or two of products have been tried and tested.

![]()

Intel Optane Memory setup, usage, and performance

The Optane Memory module looks nearly identical to any common M.2 SSD and you'd need to know what you're looking for to tell them apart. There aren't many chips on the PCB - the entire back and nearly a third of the front are empty. The module is a tiny fraction of the size of desktop 3.5-inch hard drives - its width is less than a hard drive's thickness.

One point to note is that there are two notches on the edge connector. These are called keys, and they help make sure that different kinds of M.2 modules are used in the right kinds of systems. Most people will only deal with SSDs which have one notch in what's called the 'M' position which means they use PCIe x4 bandwidth, but Optane Memory modules have notches in both the 'M' and 'B' positions. This means it uses PCIe x2 bandwidth but will work in slots designed for x4 modules.

You'll need a 64-bit installation of Windows 10 with administrator privileges in addition to the hardware requirements. You can choose to install Windows from scratch and set up the Optane Memory module in one go or plug a module into a PC with Windows already installed and running. If you choose the first option, you'll need to create a new Windows installation USB drive and edit Intel's drivers into it (instructions are provided in video and text form on Intel's website, but you have to dig a bit to find them).

We used the latter method on our test bench, consisting of Intel's brand new Core i9-7900X processor, the Asus ROG Strix X299-E Gaming motherboard, 32GB of Corsair Vengeance LED DDR4 RAM, a Cooler Master Masterliquid 240 cooler, Corsair RM650 power supply, and XFX Radeon R9 380X graphics card. Windows 10 was installed on a 4TB WD Red 40EFRX hard drive. We chose high-end components because of the Kaby Lake compatibility floor and to make sure that nothing else was bottlenecking the storage subsystem.

If you just plug the Optane Memory module into an existing PC, it will first show up in the Windows Disk Management Console as a normal drive. You can format it and assign it a drive letter, and you'll end up with a capacity of 27.12GB. We did this and ran our standard CrystalDiskMark test just to see how 3D Xpoint performs. We also ran the same tests on the hard drive as a baseline. You can see the staggering differences between the two in the table below. What's interesting to note is that the Optane Memory module was much better at reading than writing overall. It vastly exceeded the performance of standard SATA SSDs in most respects, and gave the PCIe-based Kingston KC1000 a run for its money as well.

| MBps (higher is better) | Hard Drive Only | Optane Memory as SSD | Hard Drive + Optane Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Q32T1 Read | 143.1 | 1408 | 1412 |

| Sequential Q32T1 Write | 145.6 | 297.8 | 298.6 |

| 4K Q32T1 Read | 1.694 | 908.1 | 627.5 |

| 4K Q32T1 Write | 1.685 | 284.7 | 285 |

| Sequential Read | 143.8 | 1268 | 1264 |

| Sequential Write | 143 | 292.2 | 292.6 |

| 4K Read | 0.548 | 270.2 | 191.7 |

| 4K Write | 1.592 | 128.5 | 125.9 |

Of course you only get 32GB, which makes this device completely unsuitable for use as a normal SSD despite the fact that it's possible. What you need to do is download and install Intel's Rapid Storage Technology software which includes Optane drivers. The process takes a few minutes and involves a few reboots. During this time an Optane control will need to be turned on in the system BIOS, which should happen automatically on most modern systems. When you've rebooted for the last time, fire up the Optane console and click a button to turn it on. Once everything is done, the module will disappear from the Drive Management Console and become invisible to users.

Windows will then begin optimising your files and monitoring your usage patterns to decide what should be cached on the Optane module for quicker access. Applications need to be run a few times before the driver will kick in and decide they need to be cached. For some reason, it's incredibly easy to disable the Optane drive by accident - it only takes a single click and there's no confirmation dialog. It can be turned back on in a few minutes, but this will begin the optimisation process from scratch.

We used our test system normally and allowed it to index files, hopefully analysing our usage patterns. Our first test was boot times - after shutting down the PC completely, we booted three times and recorded 21.23 to 22.49 seconds across three attempts, using a stopwatch. For reference, booting before installing the Optane Memory module took between 32.9 and 54.17 seconds.

![]()

We also copied a folder of assorted files totalling 31.4GB from a Samsung T1 USB 3.0 SSD onto our test PC. It took 4 minutes, 21 seconds without the Optane module, and 2 minutes, 42 seconds with it. When monitoring the process, we could see the Optane-enabled system maintaining speeds touching 300MBps for a while and then staying above 200MBps almost till the end, while the hard drive alone quickly filled its own 64MB cache and then dropped to about 100MBps thereafter, taking a lot longer. The Optane Memory module is intercepting writes and then pushing the data onto the hard drive when it can - this is transparent to users, who only see that they can get on with the rest of their work quicker.

After that, we measured how long it took for a few programs to load. Using PassMark AppTimer, we chose the Internet Explorer executable as a representation of a relatively small program. We got an average of 0.124 seconds, as opposed to 0.749 seconds without Optane. Finally, we measured load times for Far Cry 4, a large game. It took 1 minute, 8 seconds with Optane and 1 minute 16 seconds without - not a huge difference. The Optane driver might have decided that this game was too large to cache, or it might have decided that we hadn't used it often enough in the time that we had. Unfortunately, there's no way for a user to know what is and isn't deemed important, or manually select files and apps to be prioritised.

All of this shows us that storage subsystem performance is indeed sped up greatly for a PC with an Optane Memory module as opposed to one with just a hard drive. However, we still have to balance performance with cost and real-world practicality.

![]()

The bigger picture

Optane Memory would have been ideal for people looking to upgrade old, weak desktops without the fuss of reinstalling Windows, but it isn't compatible with anything older than Kaby Lake. Many laptops sold over the past year already have an SSD, and it's fair to assume that low-end ones with hard drives are extremely unlikely to have a free M.2 slot. This rules the upgrade market out, at least for a few years - by which time SSDs will be even more affordable.

Anyone building a new PC today will also find Optane pointless because 120GB and 240GB SSDs actually cost less than 16GB and 32GB Optane Memory modules. With Indian taxes factored in, we're seeing retail prices of Rs.4,300 and Rs. 8,000 for the 16GB and 32GB versions respectively. Intel needs the combination of Optane and a hard drive to cost less than or at least the same amount as these SSDs if it wants to convince people that they're getting the best of both worlds - speed and capacity. However, at current prices, Optane Memory makes no sense. You're better off buying more RAM or an SSD large enough to install your OS and applications on. Maybe some people will have workloads that benefit specifically from Optane's performance characteristics, but that's really reaching.

As far as pre-built desktops and laptops go, it's unlikely that manufacturers will be happy to deal with the additional setup required and the cost and complexity of dealing with two components rather than one SSD. Then there's also the need to educate customers and deal with another thing potentially going wrong. We might see such models in the market soon because anything that promises better speed has a chance of standing out, but buyers should consider carefully whether these are cost effective.

Verdict

While Optane is a fascinating new technology development and gives us a tantalising glimpse of the future, it is nowhere near its promised potential yet. In a world without SSDs, Optane Memory would do exactly what it is supposed to, but right now, its appeal is too niche and the implementation is too expensive. Unless Intel starts giving these away for free, Optane Memory in its current form will remain a solution to a problem that no one has.

Intel Optane Memory

Price: 16GB: Rs. 3,400 + GST; 32GB: Rs. 6,000 + GST

Pros

- Significant speed gains for PCs with just a hard drive

Cons

- Unreasonably expensive

- Requires at least a 7th Gen Core platform and an M.2 slot

- No benefit for PCs with an SSD

Ratings (Out of 5)

- Performance: 5

- Value for Money: 1

- Overall: 2.5

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Realme C83 5G

- Nothing Phone 4a Pro

- Infinix Note 60 Ultra

- Nothing Phone 4a

- Honor 600 Lite

- Nubia Neo 5 GT

- Realme Narzo Power 5G

- Vivo X300 FE

- MacBook Neo

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- Tecno Megapad 2

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Tecno Watch GT 1S

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)