USB Type-C, the supposedly magical new standard that promises to

solve all our connectivity problems, is finally real and ready for

mainstream use. Type-C has been in development for a while - we first

heard about it over a year ago and first saw it in action at CES in

January. Now, with the high-profile launch of Apple's new

ultra-minimalist MacBook, Type-C has gone public in a big way.

Type-C

is meant to be able to work with all kinds of devices. More

importantly, the same plug will be used on both sides of the cable and

it is symmetrical so it can go in no matter which way is up. Users are often frustrated by USB plugs because they can't tell with a

glance which way they should fit. Type-C was designed with exactly that

in mind.

But there's a lot more going on under the hood, and there

are going to be new problems. For starters, laptops can be charged

using Type-C just like phones and tablets use USB today, but not all

hosts will be able to deliver that much power. Type-C will replace

dedicated HDMI, DisplayPort and VGA video outputs on many devices, but

that doesn't mean all devices with Type-C can be plugged into screens or

projectors.

If you're wondering what exactly this new standard means for you, we have all the answers.

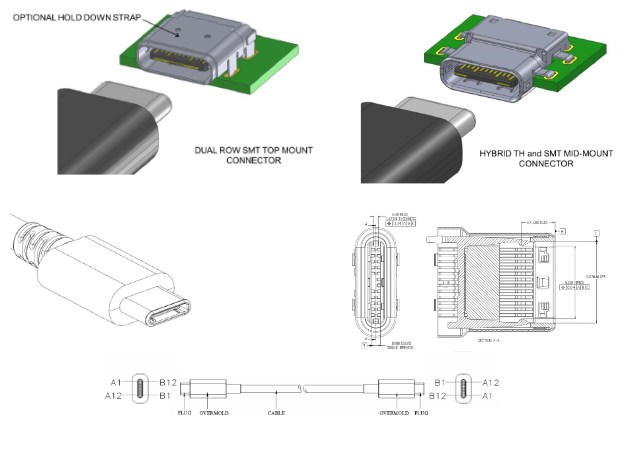

The new USB Type-C connector in all its glory.

The new USB Type-C connector in all its glory.The background

USB

1.0 and 1.1 ports first started appearing on PCs in the late 1990s and

it didn't take very long for the new standard catch on. USB provided an

alternative to the mess of serial, parallel, PS/2 and MIDI ports a PC

user typically had to deal with, but its most attractive feature was the

ability to hot-plug devices. This meant that users did not have to shut

down their PCs before making hardware changes, as had been the norm.

Data transfer speed topped out at 12Mbps, which was enough for things like input devices and printers.

USB 2.0,

which debuted in the early 2000s, raised the speed to 480Mbps, ushering in a whole new generation of storage devices and peripherals.

This is when USB emerged as a viable standard for transferring data to

and from devices such as portable media players and mobile phones.

Battery charging was a natural extension, and so the standard evolved to

improve power delivery. Experiments were made towards a wireless USB

standard, but did not really go anywhere due to power requirements and

limited flexibility.

USB 3.0 came out in 2008 in response to

standards such as FireWire and eSATA that were better at high-speed

bi-directional data transfers. Peak theoretical speed was raised to

5Gbps and for the first time, new cables and sockets were required. USB

3.0 ports and plugs were designed to be backwards compatible with older

devices, which increased their size and cost to implement. However, there was no major disruption and users were not confused.

USB 3.0 Type-A plug (top-left), USB 3.0 Type-B plug (top-right), USB 3.0 micro-B plug (bottom-left), and USB Type-C and Type-A ports (bottom-right).

USB 3.0 Type-A plug (top-left), USB 3.0 Type-B plug (top-right), USB 3.0 micro-B plug (bottom-left), and USB Type-C and Type-A ports (bottom-right).Less

than five years later, USB 3.1 was released to double the peak speed to

10Gbps, using the same plugs and ports as USB 3.0. At this point the standard changed again, but not the connectors.

To make things a little more interesting, the label "USB 3.1"

now applies retrospectively to 5Gbps USB 3.0 connections as well. The

terms "USB 3.1 Gen 1" and "USB 3.1 Gen 2" are being used to refer to

5Gbps and 10Gbps implementations respectively. Apple, for instance,

describes the 5Gbps Type-C port on its new Macbook as USB 3.1 which is

technically correct but also somewhat disingenuous.

It's

impossible to imagine a world without USB - we would still have to

depend on special-purpose plugs and ports for each kind of device.

Charging devices, syncing data and transporting anything would be a

nightmare of incompatibilities. In the age of USB, we have largely done

away with installing drivers and rebooting each time we plugged a new

device in to our PC - and if you can't remember an age when this was the

norm, consider yourself very lucky indeed.

Introducing USB Type-C

First

of all, Type-C is not a new version of USB and does not replace USB 3.0

or 2.0. Type-C refers to the plug itself, and it is just a new possible

interface for USB 3.1 (which now encompasses USB 3.0 as well). USB 3.1

will also be implemented with traditionally shaped USB ports and cables.

Type-C will very commonly be associated with USB 3.1 but it is by no

means guaranteed that a device supporting USB 3.1 speeds will use the

Type-C connector, and vice versa.

Type-C will supplant the Type-A

and Type-B connector types, which have until now been used to define the

roles of USB host and target devices respectively. Standard USB cables

were designed to have different connectors on either end to prevent

people from doing things such as plugging one printer into another and

expecting them to work without anyone sending print commands. Worse,

people might have plugged two power sources into each other. It's for

this exact reason that power cables have always had different plugs on

each end - and so such problems have rarely arisen, if ever.

Over

the years, Mini-B and then Micro-B emerged to cater to increasingly

smaller devices (more commonly known as Mini-USB and Micro-USB

respectively). However, at the same time, devices once intended to be

targets began to take on aspects of host devices. We wanted to be able

to plug pen drives into smartphones, print directly from storage

devices, and use touchscreen tablets as control surfaces, amongst other

things. USB On-the-Go (OTG) allowed devices to host other target devices

through their Type-B ports. However, dongles were needed because of the

different port shapes, which meant the potential of the technology was

rarely realised.

Now, we'll be able to plug anything in to

anything else. Theoretically, devices will sense each other and clearly

establish what they expect of each other in terms of charging, control

and data exchanges. Incompatible products just won't work - people will

still get frustrated, but hopefully not too much. In this sense, Type-C

trades one set of problems for another.

In Part 2, we get into Alternate Modes and enhanced power delivery, which are unique to Type-C, and take a look at some of the hardware that will soon be commonplace.

Everything You Need to Know Before Buying a Soundbar31 January 2019

Everything You Need to Know Before Buying a Soundbar31 January 2019 Tech 101: What Is Spectrum, and Why Is It Being Auctioned?31 July 2016

Tech 101: What Is Spectrum, and Why Is It Being Auctioned?31 July 2016 The Private/ Incognito Mode in Your Browser - What It Does and Does Not Do15 December 2015

The Private/ Incognito Mode in Your Browser - What It Does and Does Not Do15 December 2015 The Best Wireless Headphones and Our Picks for Gaming, Noise Cancellation, and More14 December 2015

The Best Wireless Headphones and Our Picks for Gaming, Noise Cancellation, and More14 December 2015 Headphones 101: Choosing the Right Type of Drivers27 November 2015

Headphones 101: Choosing the Right Type of Drivers27 November 2015

![Gadgets 360 With Technical Guruji: News of the Week [April 12, 2024]](https://c.ndtvimg.com/2025-04/jlpk5kco_news-of-the-week_160x120_12_April_25.jpg?downsize=180:*)