- Home

- Internet

- Internet News

- Meet the apprentices of the digital age

Meet the apprentices of the digital age

Gao decided that she didn't want to continue studying at Baruch College, part of the City University of New York. At first she considered transferring to Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, but she changed her mind when she saw that her tuition bill would be around $44,000 a year, with only a small amount of financial aid available. "I didn't want to come out of college with $200,000 in debt and have to spend 10 years paying it off," she said.

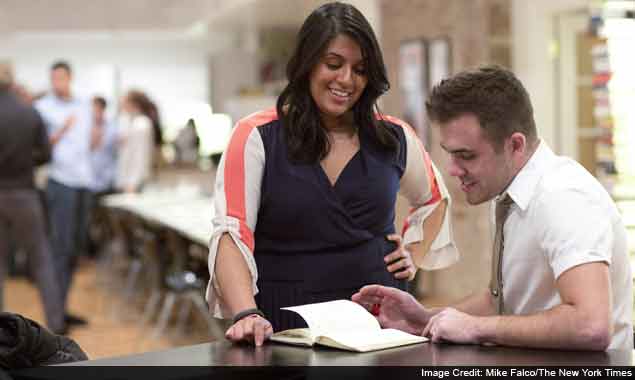

Yet she still sought a way to nurture her interest in technology. A year later, Gao holds the title of data strategist at Bitly, the URL-shortening service based in New York.

How did she catapult from dropping out of college to landing a plum job? She became an apprentice to Hilary Mason, chief data scientist at Bitly, through a new two-year program called Enstitute. It teaches skills in fields like information technology, computer programming and app building through on-the-job experience. Enstitute seeks to challenge the conventional wisdom that top professional jobs always require a bachelor's degree - at least for a small group of the young, digital elite.

"Our long-term vision is that this becomes an acceptable alternative to college," says Kane Sarhan, one of Enstitute's founders. "Our big recruitment effort is at high schools and universities. We are targeting people who are not interested in going to school, school is not the right fit for them, or they can't afford school."

The Enstitute concept taps into a larger cultural conversation about the value of college - a debate that has heated up in the last few years. In important ways, the value is indisputable. The wage gap between college graduates and those with just a high school degree is vast in 2010, median earnings for those with a bachelor's degree were more than 50 percent higher than for those with only a high school diploma, according to the Department of Education.

But college is expensive, and becoming more so - between 2000 and 2011, tuition rose 42 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics - and students fear being saddled by debt in a bleak job market. (Students from the class of 2011 who took out loans graduated with an average debt of $26,000.) And some employers complain that many colleges don't teach the kinds of technical skills they want in entry-level hires.

Peter Thiel, the billionaire investor, upped the ante to this argument when he started the Thiel Fellowship, which pays a no-strings-attached grant of $100,000 for young people not to attend college and to pursue their entrepreneurial dreams instead.

Enstitute doesn't offer anything like $100,000 to its apprentices. Still, it is aimed at intelligent, ambitious and entrepreneurial types - people like Gao, who participated in the Technovation Challenge, a nine-week program and competition for high school girls to design a mobile app prototype at Google in New York.

"If I had known at 19 what Jasmine knows, I would be ruling the world," says Mason, who is 34.

The concept is not a perfect model by any stretch. For one thing, a college degree is still the assumed prerequisite of most any professional job. But more people seem interested in testing alternatives.

"We need educational research and development for a new time," says Tony Wagner, an innovation education fellow at the Technology and Entrepreneurship Center at Harvard and the author of "Creating Innovators."

"I have no idea whether Enstitute is going to be successful," he adds. The only way to find out, he says, would be to follow the apprentices over time after the program and compare them with their college-educated peers. "Yes, you get exposed to a lot of great things by going to a liberal arts school," Wagner says, "but you have to look at the cost-benefit analysis."

Bypassing college

Sarhan and his co-founder, Shaila Ittycheria, met when they worked at LocalResponse, a social media company in New York. They selected this year's first class of fellows - 11 in all - from a national pool of 500 applicants ranging in age from 18 to 24.

Ittycheria, 31, and Sarhan, 26, call the program "learning by doing." Students train under a master, in the way that many trade professions have operated for centuries. "It's a level of experience that an intern never sees," Ittycheria says.

For participating companies, the program offers cheap, talented labor for a much longer period than a typical internship. But the fellows are betting that their minimal wages will turn into full-time jobs once they complete the program - perhaps even at the very company where they apprenticed.

Nine of the fellows have attended at least one year of college, and three are college graduates. Most say they do not plan to return to school. But what will the apprentices miss if they forgo the four-year period of intellectual exploration and cultural knowledge that college is meant to provide? Defenders of higher education argue that college students gain important knowledge as well as critical-thinking skills that are crucial to a meaningful life and career.

The Enstitute's founders contend that their program does teach critical thinking, but in different ways. "They are not debating Chaucer; they are debating product features," says Sarhan, who graduated from Pace University. "But it's the same idea of how do I write down and communicate an argument."

Enstitute does offer a semiformal curriculum, requiring eight hours a week on topics like finance branding, computer programming and graphic design, as well as English, sociology, and history, the content of which comes largely from online courses. The fellows also receive writing assignments every six weeks; outside academics and experts edit and review the work for writing style and grammar. Many fellows choose a less technical track for their course work and study subjects like Japanese culture or the poetry of Keats.

Based on their living arrangements, it would be easy to mistake the fellows for traditional college students. They share a large loft space at 11 Stone Street, near the southern tip of Manhattan. There are two to four beds to a room and three shared bathrooms, and the fellows share cleaning duties.

Most socializing takes place in a sparsely decorated common space, and around a large banquet-type table. Dinners are usually prepared and eaten communally. Twice a week, established entrepreneurs come to dinner, give an informal talk and take questions.

Perhaps the only giveaway that this isn't a college dorm is that by Friday night, the apprentices are often too tired to go out. Full-time work is exhausting.

Many of the fellows say they work upward of 40 hours a week. There is no overtime; the compensation package is a stipend, usually around $800 a month, with housing and food fully subsidized by Enstitute - a benefit being extended only to the program's first class. Starting this September, the new batch of fellows will have to pay $1,500 in annual tuition, and their room and board will not be covered. Stipends, however, will be around $1,600 a month - and they will be paid overtime.

The entrepreneurs cite various reasons for agreeing to take on an apprentice. "It's an awesome value at a nominal cost," says Ben Lerer, 31, a co-founder of the Thrillist Media Group, a digital media site geared toward men; its apprentice is Ben Darr, 20. "We would hire Ben full time today," says Lerer, who treats Darr to twice-weekly boxing sessions. (Enstitute strongly discourages employers from hiring the apprentice before the program is over.)

Having an apprentice for a two years has other advantages for a business. "It takes three to four months before you trust an intern and before they are up to speed, and then the internship is over," Lerer says.

Mason, at Bitly, agreed to participate in the program because she has an intellectual interest in new models of education. "I moved from academia into startups, and I wish I had had a way to learn what I needed to be useful at a company," says Mason, a former computer science professor at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, R.I.

Beyond the fellows' work, companies are eager to tap into the mindset of 18- to 24-year-olds, a coveted demographic group.

Kwame Henderson, 23, an apprentice at the mobile software company Tracks, is its head of quality assurance and manages a product plan, which involves ensuring that the app works properly for users across all their devices.

"Kwame put together a whole presentation of how people in college would use Tracks, says the company's founder, Vic Singh, 36. He makes copy sound more casual, and that helps move the needle with the younger audience."

(Unlike most of the fellows, Henderson is a college graduate; he received a bachelor's degree in marketing, with a minor in information technology, from Seton Hall in 2011. He enrolled in Enstitute as an alternative to attending an MBA program, which would have cost $50,000 a year.)

Job prospects

The apprenticeships in this class focus on tech startups. For the next class, Enstitute will offer apprenticeships in digital advertising and nonprofit areas, placing fellows at places like The New Republic, The Huffington Post, BuzzFeed and the nonprofit Charity: Water.

Enstitute says it has raised around $300,000 in donations in the last year, and it plans to expand to a couple of more cities by fall 2014. Its founders want the nonprofit Enstitute to become a brand name like that of a top-flight university. But instead of getting a paper diploma, fellows will graduate with a portfolio of skills they've acquired, business development deals they've closed, marketing materials they've created and products they've built, in addition to five to 10 recommendations.

When the first Enstitute graduates enter the job market, some hiring managers might view the program skeptically, says John Sullivan, a management professor of at San Francisco State University who serves as a hiring consultant for technology companies. Many hiring managers still place a high premium on a college degree and will not even consider an applicant without one, he says.

But many companies are having trouble filling positions requiring precisely the kind of knowledge that the apprentices are learning. Henderson plans to leave Tracks knowing how to ensure that a mobile app is ready for public release. Darr learned how to wireframe, a way of making prototypes for screen-based products. Gao, who wants to run her own company, is learning Python, a coding language. Samman Chaudhary, 24, who wants to work at a business incubator, will have experience in evaluating business plans; she recently judged a venture capital investment competition at the Stern School of Business of New York University.

"It's a race for top talent, and you would be crazy to ignore talent that is demonstrating execution and learning through alternative channels," says Jason Madhosingh, an Enstitute board member and director of innovation and digital partnerships at American Express, a role in which he makes hiring decisions.

For many companies in technology hubs like Silicon Valley, San Francisco and New York, though, "this is exactly the kind of hire they are looking for," Sullivan says. "Code speaks louder than words there."

© 2013, The New York Times News Service

For the latest tech news and reviews, follow Gadgets 360 on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News. For the latest videos on gadgets and tech, subscribe to our YouTube channel. If you want to know everything about top influencers, follow our in-house Who'sThat360 on Instagram and YouTube.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025

- ChatGPT

- Redmi Note 14 Pro+

- iPhone 16

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Moto G15 Power

- Moto G15

- Realme 14x 5G

- Poco M7 Pro 5G

- Poco C75 5G

- Vivo Y300 (China)

- HMD Arc

- Lava Blaze Duo 5G

- Asus Zenbook S 14

- MacBook Pro 16-inch (M4 Max, 2024)

- Honor Pad V9

- Tecno Megapad 11

- Redmi Watch 5

- Huawei Watch Ultimate Design

- Sony 65 Inches Ultra HD (4K) LED Smart TV (KD-65X74L)

- TCL 55 Inches Ultra HD (4K) LED Smart TV (55C61B)

- Sony PlayStation 5 Pro

- Sony PlayStation 5 Slim Digital Edition

- Blue Star 1.5 Ton 3 Star Inverter Split AC (IC318DNUHC)

- Blue Star 1.5 Ton 3 Star Inverter Split AC (IA318VKU)