- Home

- Internet

- Internet News

- Feed the Beast (Or Else)

Feed the Beast (Or Else)

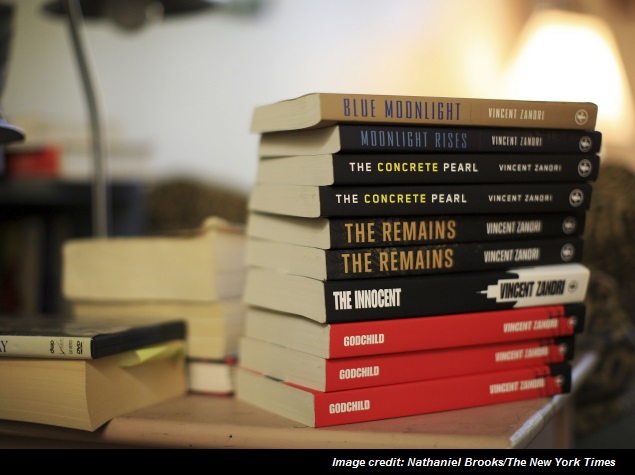

Zandri, an author of mystery and suspense tales, is published by Thomas & Mercer, one of Amazon Publishing's many book imprints. He is edited by Amazon editors and promoted by Amazon publicists to Amazon customers, nearly all of whom read his books in electronic form on Amazon's ereaders, Amazon's tablets and, soon, Amazon's phones.

His novels are not sold in bookstores and rarely found in public libraries. His reviews are written by Amazon readers on the Amazon website. "Has a little bit of something for everyone," one enthusiast exclaimed. "Heavy machinery, love, humor and mystery." And his latest prize was an award from Amazon.

It is the 21st-century equivalent of living in a company town, but Zandri, 50, is far from a downtrodden worker.

A few years ago he was reduced to returning bottles and cans for grocery money. Now his Amazon earnings pay for lengthy stays in Italy and Paris, as well as expeditions to the real Amazon.

"I go wherever I want, do whatever I want and live however I want," he said recently at a bar in Mill Valley, California, a San Francisco suburb where he was relaxing after a jaunt to Nepal.

While Zandri celebrates Amazon as the best thing to happen to storytellers since the invention of movable type, many other writers are denouncing what they see as its bullying tendencies and an inclination toward monopoly.

From household names to deeply obscure scribblers, authors are inflamed this summer, perhaps more deeply divided than at any point in nearly a half-century. Back then, it was the question of being a hawk or dove on Vietnam. Now it is not a war but an Internet retailer and its unparalleled grip on the cultural machinery that is provoking fierce controversy.

At first, those in the publishing business considered Amazon a cute toy (you could see a book's exact sales ranking!) and a useful counterweight to Barnes & Noble and Borders, chains willing to throw their weight around. Now Borders is dead, Barnes & Noble is weak and Amazon owns the publishing platform of the digital era. The company founded and still run by Jeff Bezos dragged the publishers into modern times, forced them to digitize and urged on the Justice Department in its 2012 antitrust suit against the publishers and Apple. The conflict is unrelenting.

The latest struggle between publishers and Amazon burst into public view two months ago, after the company began seeking concessions on book sales from Hachette, the fourth-largest publisher, which Hachette was unwilling to give. Amazon sought to get its way by delaying delivery of Hachette books, which roused Hachette's authors. At this point, Hachette is losing sales and Amazon is reaping a considerable amount of bad publicity.

All of this angst and arguing is pushing forward a question: Is the resistance to Amazon a last-ditch bid to keep the future of American literary culture out of the hands of a rapacious corporation that calls books "demand-weighted units," or an effort by a bunch of dead-enders and snobs to forestall a future that will be much better for most readers and writers?

Zandri, who 15 years ago had a $235,000 contract with a big New York house that went sour, has an answer.

"Everything Amazon has promised me, it has fulfilled - and more," he said. "They ask: 'Are you happy, Vince? We just want to see you writing books.' That's the major difference between corporate-driven Big Five publishers, where the writer is not the most important ingredient in the soup, and Amazon Publishing, which places its writers on a pedestal."

It sounds alluring. This is the siren call of the modern tech colossus, not just Amazon but Google, Apple and Facebook - companies with bottomless pocketbooks and infinite ambitions: We're building a better world. It will be dedicated to fulfilling all your needs and desires, including the ones you didn't even know you had. Trust us.

'Ruthlessly Efficient'

Amazon offers a vast array of goods. It is easy to order from. It is inexpensive. Everything arrives promptly. Customers love it. To no one's surprise, Amazon is now one of the 10 biggest retailers in the United States, edging out the 99-year-old Safeway grocery chain.

Things are cheap for a reason, however. Inspired by Wal-Mart, Amazon takes a famously hard line toward the people who make the stuff it sells.

"Amazon is not evil, but it is ruthlessly, ruthlessly efficient," said Andrew Rhomberg, founder of JellyBooks, an ebook discovery site. "As consumers, we love Amazon's efficiency and low prices," he said. "But as suppliers, it is a toad that is hard to swallow."

For Hachette, which publishes under the Little Brown and Grand Central imprints, the latest proposal was more elephant than toad. Both parties have declined to say exactly what Amazon is asking; the general belief is that it wants to increase its share of revenue on every ebook to 50 percent from 30 percent.

Amazon believes that publishers take too much of the money in producing a book and add too little value. In traditional publishing, the highest royalty a writer could get was 15 percent of the book's price. With ebooks, the royalty is 25 percent of net revenue, but Amazon feels that is still not enough. Zandri gets 35 percent, and self-published writers who use Amazon's platform get more.

"Amazon believes the value exchange between publishers and authors is fundamentally broken," said Scott Jacobson, who worked on the Kindle team at Amazon and is now at the Madrona Venture Group. "In a world where authors can hire their own editors, market their books through the Web and social media, and get production and distribution through Amazon or other services, publishers will play a lesser role and their share of the economics will be diminished."

So writers should get more and publishers less, an assertion with which few writers would disagree. But Amazon also believes that books should be cheap. This makes the pie smaller for everyone; Amazon argues that the publishers will make up on volume what they lose on each sale.

In interviews, for the first time, executives from Amazon and Hachette explicitly described their positions.

"If you charge high ebook prices, ultimately what you're doing is making a slow, painful slide to irrelevancy," said Russell Grandinetti, Amazon's senior vice president for Kindle. "You have to draw the box big. Books don't just compete against books. Books compete against Candy Crush, Twitter, Facebook, streaming movies, newspapers you can read for free. It's a new world. It's so important not to simply build a moat around the industry the way it is now."

Amazon favors a price of $9.99 for many ebook titles, while Hachette and other publishers want to charge more. Sixty percent of Hachette's ebook sales in the United States occur on Amazon.

"For most books, $9.99 creates more total revenue than $14.99," Grandinetti said. "That means $9.99 creates more total dollars to share with authors."

Amazon also argues that publishers like Hachette are ungrateful. They are generally doing well now, thanks to the fact that ebook income is bolstering their bottom line. And who made that ebook income possible?

"The truth is, Hachette is making dramatically larger profits on digital sales in large part thanks to Kindle, which has led the book business to a very healthy transition to digital, perhaps uniquely among media," Grandinetti said.

Hachette says Amazon is merely trying to plug the holes in its bottom line.

"This controversy shouldn't be misinterpreted," said Michael Pietsch, chief executive of the Hachette Book Group. "It's all about Amazon trying to make more money."

He noted that Amazon was also trying to squeeze a large publishing group in Germany, Bonnier, for better terms. And Germany has fixed-price laws for books. That, Pietsch said, "is evidence that Amazon's margins, not lower prices for consumers, are the crux here."

Shares of Amazon have been under pressure this year. Amazon's vast ambitions are not prompting the sort of unrestrained excitement on Wall Street that they used to.

"You always hear about never wanting to fight a two-front war," said John Rossman, a former Amazon executive. "Well, Amazon is fighting a five-front war. They are investing in faster delivery, in a phone, in streaming video. And they need more profits so they can continue their investments. That's why there is a lot of pressure and negotiation."

Pietsch implied that Amazon was becoming desperate.

"You can't blame shareholders for demanding, at long last, a normal return on their investment," he said. He added that even as Amazon was publicly accusing Hachette of refusing to negotiate last week, the publisher was putting its third proposal on the table, "by far the most generous to date."

A deal soon would not be a surprise.

A Changing World

It wasn't always this hard for Amazon to bend publishers to its will.

A decade ago, when all books were physical, Amazon would run the numbers on its suppliers and would notice that one publisher was out of line - perhaps not paying the same amount to Amazon to promote its titles as some of its peers.

So Amazon would talk with the publisher, try to make it see reason. Sometimes it did not. Publishers were arrogant back then, said Randy Miller, who worked at Amazon from 1999 to 2006.

"A lot of people had been in business for 30 years," he said. "They said: This is what we're going to publish, this is the price, you have no leverage, we control the content."

They had no clue that the world was changing. If a publisher did not give Amazon what it wanted, some of its books might disappear from the site. The writers would go wild.

"There were particular authors - we'd meet with them, have dinner with them - and they'd say, 'I always check Amazon to see where my book is,'" Miller said. "They'd do it over their morning coffee. So you knew."

Among the buttons Amazon could push: raise the price, recommend something cheaper, make the book disappear from promotional lists.

"If I pull you out of recommendations, customers aren't going to see you at all," said Miller, who remembers doing just that as the executive in charge of buying operations and vendor management for Europe. "It was the equivalent of a physical store putting you back by the discounted gardening equipment, where no one will ever find you."

Miller recalled a publisher taking six months to give in after this sort of treatment, which, he stressed, Amazon undertook only rarely.

Others saw the light faster.

"An author would see his ranking drop from 98 to 798, and the first thing he'd do is call his agent or publisher and say, 'What happened?' " he said. "He held the publisher responsible and expected it to straighten this out."

In the Hachette dispute, authors are also bent out of shape, but see the villain this time as Amazon. And they are complaining on Twitter and Facebook. As Miller put it, "It seems like every day another author gets a torch and heads to the castle."

This month, an unhappy group of writers issued a petition portraying the retailer as inconveniencing and misleading its own customers in the dispute, and thus "contradicting its own written promise to be 'Earth's most customer-centric company.'" In an emotional plea, the writers go on to accuse Amazon of betrayal.

"This is no way to treat a business partner," says the petition, which has been signed by big-name authors from Stephen King to Robert Caro. "Nor is it the right way to treat your friends."

All of that criticism puts Amazon, which is positioning itself as the authors' champion, in an awkward position. Last week, the retailer issued a sharply worded statement that Hachette "should stop using their authors as human shields."

'Waiting for Moses'

Smaller publishers are watching the standoff with anxiety, if not outright dread.

"I feel as if we're seeing a shift in the paradigm of publishing right before our very eyes," said Marlie Wasserman, director of Rutgers University Press.

With titles like "Queering Marriage: Challenging Family Formation in the United States" or "Embodying Culture: Pregnancy in Japan and Israel," Rutgers books tended to be invisible before Amazon.

"Amazon has democratized shelf space," Wasserman said. "In the last five years, not a single author complained to me that he couldn't find his books at a physical store. That's not where the action is anymore. I have to consider this every time I hear that Amazon is a bully."

Amazon is now responsible for 72 percent of Rutgers' ebook sales, and a third of its $3 million in annual revenue. If only the retailer were a little easier to deal with: At Rutgers, as with most presses, communicating with Amazon means communicating through a web interface. There is no sense there is a person at the other end.

"We still pride ourselves on what we are doing - producing books that educate and create a public good," Wasserman said. "To see that migrate into the hands of people who might not share our mission, or might not even be people, doesn't say much for the future of American culture."

Academic houses traditionally sell their books, which are labor-intensive and printed in small quantities, for smaller discounts than general publishers do. Amazon will have none of that. "I offered them a 30 percent discount, and they demanded 40," said Karen Christensen of Berkshire Publishing, a small academic house in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

Amazon, as usual, got what it wanted. Then it asked for 45 percent.

"Where do I find that 5 percent?" Christensen asked. "Amazon may be able to operate at a loss, but I'm not in a position to do that."

Christensen, like other publishers, complains that Amazon is very inventive with fees and charges that rapidly add up.

But at the same time, Amazon has made itself essential to Berkshire, which publishes a three-volume dictionary of Chinese biography that sells for $595. Amazon is responsible for about 15 percent of Berkshire's business. Christensen feels that she can't leave Amazon but fears what else it might ask.

"I wake up every single day knowing Amazon might make new, impossible demands," she said.

Amazon has been reported to be seeking a new concession from publishers: If a customer orders a book and it is not immediately available, it wants the right to print the volume itself. An Amazon spokesman said it does not compel publishers to use the technology but offers it as a service. The customer wants the book immediately, so this makes obvious sense. But it chips away yet again at the publisher's role.

"We're all sort of looking around now, waiting for Moses," said another university press director. As a measure of the anxiety inspired by Amazon, he was unwilling to make a statement on the record.

Moses would somehow make the Amazon juggernaut stumble, preserving the good parts while getting rid of the bad. Another antitrust suit, this time supporting the publishers rather than going after them, might fill the bill nicely.

"I can see the emotional argument against Amazon, but I have a hard time seeing it prevail in court," said Geoffrey A. Manne, executive director of the International Center for Law and Economics in Portland, Oregon. "The argument that there is an appropriate number of competitors, and one is not it, almost never flies in the United States."

American publishers and booksellers are looking longingly at France, where different rules apply. In late June, the French Senate unanimously passed a law forbidding free shipping on books bought online. It was called the Anti-Amazon Law.

'Soon, Amazon Mars'

Three weeks ago, just before he went to Nepal, Vincent Zandri signed a contract with Amazon for a new novel, "Everything Burns." His $30,000 advance was immediately deposited in his bank account. By this point, he said, he is earning about what a junior lawyer makes at a big firm. Call it a comfortable six figures annually.

"It's traditional publishing, but better, with a higher royalty rate," he said. "I'm published by Amazon France, Amazon Germany, Amazon India. Soon, Amazon Mars." The company sent him a free Kindle, and now he gets most of his books from Amazon. Most of the movies he watches come from the site as well. "Amazon touches every bit of my life," he said.

Zandri is so embedded in Amazon that he recently started wondering about it.

Two years ago, he wrote about publishers on his blog: "I know I'm supposed to cry for these people, but they had a chance to survive and in fact thrive in today's digital book publishing world, but they haven't. And now they are going the way of the eight-track. Bon voyage."

It's not that simple anymore.

"Publishing is a shyster business," he reflected. "One day it's 'You rock, bro,' and the next day they're not returning your calls. If I'm not moving books on Amazon, they're not going to ask me back. It's not a charity."

Amazon looks so good because it has the rest of publishing to compete against. But if those publishers wither, maybe that would not be true.

Zandri can even conceive of publishing with a New York house again. They still provide some forms of legitimacy that Amazon does not, with independent reviews and a presence in bookstores.

So in the Amazon-Hachette dispute, somewhat to his surprise, he is on no one's side.

"I don't agree that the entire dismantling of the traditional publishing world in New York is the answer," he said. "No one wants to hand Amazon a monopoly. I'd be a fool to assume the good times will last forever."

© 2014 New York Times News Service

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Poco C85x 5G

- Realme Note 80

- Vivo V70 FE

- Realme C83 5G

- Nothing Phone 4a Pro

- Infinix Note 60 Ultra

- Nothing Phone 4a

- Honor 600 Lite

- MacBook Neo

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- Tecno Megapad 2

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Tecno Watch GT 1S

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)