- Home

- Internet

- Internet News

- Data security is a classroom worry, too

Data security is a classroom worry, too

Edmodo's free software allows teachers to set up virtual classrooms where they can post homework assignments, give quizzes and use third-party apps to complement lessons. Students can create individual profiles, including their photograph and other details, within their teacher's class and post comments to a communal class feed.

Porterfield, an engineer at Cisco Systems, examined Edmodo's data security practices by registering himself on the site as a fictional home-school teacher. As he went about creating imaginary students - complete with cartoon avatars - for his fictitious class; however, he noticed that Edmodo did not encrypt user sessions using a standard encryption protocol called Secure Sockets Layer.

That cryptography system, called SSL for short and used by many online banking and e-commerce sites, protects people who log in to sites over an open Wi-Fi network - like the kind offered by many coffee shops - from strangers who might be using snooping software on the same network. (An "https" at the beginning of a URL indicates SSL encryption.)

Without that encryption, Porterfield says, he worried about the potential for a stranger to gain access to student information and thus hypothetically be able to identify or even contact students.

To test this hypothesis, he used a computer on his home Wi-Fi network to log in as an imaginary student; then, using another computer, he installed free security auditing software, called Cookie Cadger, to spy on the student's online activities. Though the risk of this happening with actual students seemed small - Edmodo and other companies say they have no evidence that this kind of breach has occurred - he contacted his school district about his concerns.

"There's a lot of contextual information you could use to gain trust, to make yourself seem familiar to the child," he says. "As a parent, that's the scariest thing."

In response to an inquiry from me last week, Sara Mandel, a spokeswoman for Edmodo, said the service provided "a safe alternative to open, consumer social networking sites" because students could participate only in groups created by their teachers and because teachers decided whether students could send private messages to one another.

She added that "any school that chooses" had been able to use a completely encrypted version of the site since 2011 and that the company "is working to ensure that all of our users are using an SSL-encrypted version."

School administrators and teachers said they liked these online learning systems because they could control the information that students might share.

"Kids can't talk to each other. They can only speak to the group," says Heather Peretz, a special-education teacher at Great Neck South Middle School in Great Neck, N.Y., who uses Edmodo in her English class. "It helps them learn to be good digital citizens so they are not making inappropriate posts."

But as school districts rush to adopt learning-management systems, some privacy advocates warn that educators may be embracing the bells and whistles before mastering fundamentals like data security and privacy.

Although a federal law protecting children's online privacy requires online services to take reasonable measures to secure personal information - like names and email addresses - collected from children under 13, the law doesn't specifically require SSL encryption. Yet school districts often issue only general notices about classroom technology, leaving many parents unaware of the practices of the online learning systems their children use. Moreover, schools often require online participation so students can gain access to course assignments or collaborate on projects.

"What we are finding with this type of database is that parents are uninformed," says Khaliah Barnes, a lawyer at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. "Most don't understand how the technology works."

Online security experts have long warned consumers about unencrypted websites that collect personal details That is because on open Wi-Fi networks, hackers using simple software programs can see and copy the unique code, called a session cookie, that servers issue to authenticate a person who has logged into a website. By replicating that cookie, a hacker can acquire the same privileges, like the ability to edit a profile or grade a quiz, of the authenticated user for that session.

To call attention to this risk, a software developer in 2010 released a free program called FireSheep that was capable of hijacking unencrypted sessions of people using open Wi-Fi. Early the next year, Facebook began rolling out full encryption. But, because that kind of cryptography requires more computing power, it can slow down sites and increase costs. That is why many sites - even some dating services that ask personal questions - remain largely unencrypted.

"It's not good to trade performance for security when you are talking about people's personal information," says Michael Clarkson, an assistant professor of computer science at George Washington University who teaches an annual course on software security. "I can't think of a good reason not to keep the entire session encrypted."

Last fall, Porterfield, who was coaching his younger son's soccer team, was asked by the league to use a free youth sports site provided by Shutterfly, a photo-sharing service, to post team rosters, player contact information, game locations and player photos. He discovered that the site was not fully encrypted - an issue reported in a May article in Mother Jones. (Last Friday, a spokeswoman for Shutterfly told me that the company planned to introduce full SSL encryption on its youth sports and other sites by the end of July.) It was this that made Porterfield curious about data security practices of K-12 online learning services and led him to set up imaginary classes on several sites.

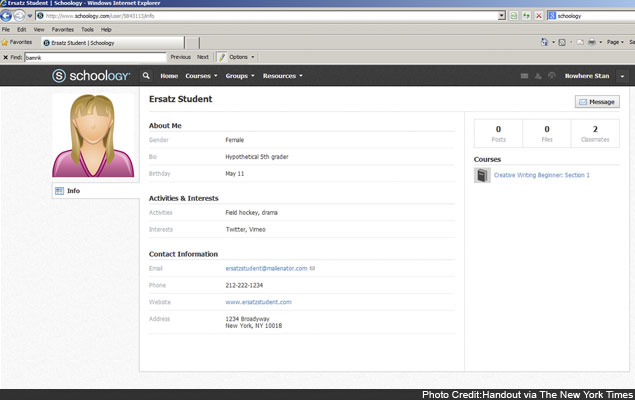

One site was Schoology, a learning network used by more than 2 million students and teachers worldwide. Its privacy policy says it "uses industry standard SSL (secure socket layer) encryption to transfer private, personal information."

Porterfield found that for the fictitious classroom he set up in May using Schoology's free software, the login page did use SSL. But the profile pages that included students' email addresses, birth dates, phone numbers and home addresses were not protected.

To check Porterfield's concerns, I asked Ashkan Soltani, an independent security analyst, to look at both Edmodo and Schoology. He found that each site's login page was encrypted, but not student sessions themselves.

"Anyone at a local cafe with Wi-Fi will have access to the information that the student is viewing or transmitting," he told me. "I would consider that potentially sensitive information from the perspective of parents."

Full-session encryption may not have seemed so important several years ago, when students logged into the sites primarily on secure networks at school or at home. But now that so many students use mobile devices, learning networks say they are moving toward full encryption.

For individual teachers who wanted to set up online groups, for instance, Schoology until last week offered free software that encrypted login pages. For customers like school districts who paid for more comprehensive packages, the site offered the option of full-session encryption. Last Monday, Jeremy Friedman, the chief executive of Schoology, told me the company planned to switch to sitewide encryption by this fall. Last Thursday evening, he emailed with an update: The sitewide encryption had just been completed.

"Ultimately, we are all working toward the same thing - protecting student data and privacy," Friedman said.

Schools are also developing methods to protect student data. The Palo Alto Unified School District in California uses Schoology as a clearinghouse for course assignments in its secondary schools and a couple of elementary schools. But administrators prevent students from entering personal data, like email addresses, in their profiles. They encourage students to upload an avatar, not a photo of themselves. And the district doesn't post grades on the site.

"We take security very seriously," says Ann Dunkin, the school district's chief technology officer, "and one way to take it seriously is to limit the amount of information students can put into the system."

But Porterfield says schools, no matter their vigilance, should be transparent with parents about the potential risks of online learning networks.

"It's not the school's decision to make," he said. "You should let the parents know."

© 2013, The New York Times News Service

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Tecno Pova Curve 2 5G

- Lava Yuva Star 3

- Honor X6d

- OPPO K14x 5G

- Samsung Galaxy F70e 5G

- iQOO 15 Ultra

- OPPO A6v 5G

- OPPO A6i+ 5G

- Asus Vivobook 16 (M1605NAQ)

- Asus Vivobook 15 (2026)

- Brave Ark 2-in-1

- Black Shark Gaming Tablet

- boAt Chrome Iris

- HMD Watch P1

- Haier H5E Series

- Acerpure Nitro Z Series 100-inch QLED TV

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)

![[Partner Content] OPPO Reno15 Series: AI Portrait Camera, Popout and First Compact Reno](https://www.gadgets360.com/static/mobile/images/spacer.png)