- Home

- Internet

- Internet News

- Booksellers Score Some Points in Amazon's Standoff With Hachette

Booksellers Score Some Points in Amazon's Standoff With Hachette

"As you can imagine, all anyone was talking about was the standoff between Hachette and Amazon," he told me this week, referring to the much-publicized impasse in contentious negotiations between the publisher and the giant Internet bookseller. "I wanted to do something positive that would take advantage of this."

The New York Times revealed last month that Amazon seemed to be discouraging sales of Hachette books by failing to stock them, delaying delivery and removing preorder buttons from its website.

Exactly what the dispute involves has been shrouded in secrecy, but price is clearly at the center. Hachette and Amazon seem to be locked in the kind of intense negotiations that are common between manufacturers and retailers in most businesses, but have attracted enormous attention because of the visibility and cultural significance of books. (Negotiations between television program suppliers and cable companies have achieved similar notoriety and have also resulted in impasses.)

(Also see: Hachette Seeking Amazon Terms That 'Value' Authors and Publishers)

I spoke to someone involved on the Hachette side of the negotiations, who is under orders not to discuss them and asked not to be named. This person said that Amazon has been demanding payments for a range of services, including the preorder button, personalized recommendations and a dedicated employee at Amazon for Hachette books. This is similar to so-called co-op arrangements with traditional retailers, like paying Barnes & Noble for placing a book in the front of the store.

Amazon "is very inventive about what we'd call standard service," this person said. "They're teasing out all these layers and saying, 'If you want that service, you'll have to pay for it.' In the end, it's very hard to know what you'd be paying. Hachette has refused, and so bit by bit, they've been taking away these services, like the preorder button, to teach Hachette a lesson."

What bothered Sindelar wasn't that Amazon's tactics were so hard-boiled. Rather, "our goal as retailers is to connect people to books," he said. "The notion that a retailer would obstruct readers from getting to certain books they want completely violates our ethics as retailers. I wondered how we could get that message across to customers."

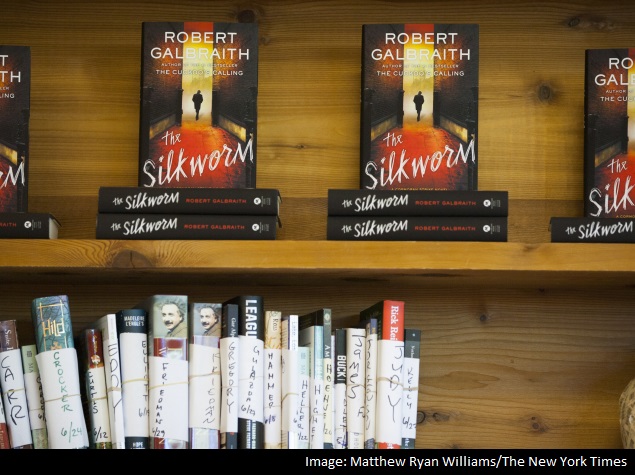

So Sindelar went to Hachette's publishing list, looking for the next potential blockbuster. At the Hachette subsidiary Little, Brown and Co., he found "The Silkworm" by Robert Galbraith - aka J.K. Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter series - the follow-up to her best-seller "The Cuckoo's Calling."

"That seemed obvious," he said. "Ordinarily, we wouldn't get any preorders for a book like that. Zero. But Amazon had deleted its preorder button, so I thought we could capitalize on that."

Third Place Books began featuring "The Silkworm" prominently on the home page of its website, offering hardcover copies at a 20 percent discount along with free, in-person delivery the day the book was released, which was Thursday.

Sindelar, along with several other store employees, delivered the books (although a surprising number of customers said not to bother - they wanted to come into the store for their copy). He also handed out what he called "Hachette swag bags" with a T-shirt and advance copy of a coming Hachette novel. Some buyers also received a surprise visit from a local author, Maria Semple, who wrote the best-selling book "Where'd You Go, Bernadette."

"I thought this would show what we as booksellers stand for," Sindelar said. "While Amazon is blocking people, we literally put the book in their hands. But we're not asking people to boycott Amazon. We're in Seattle and Amazon is a big part of the local economy. We're sensitive to that."

So Third Place Books didn't participate in the campaign to place "I didn't buy it on Amazon" stickers on books that the comedian Stephen Colbert started this month on his show on Comedy Central. (Hachette is Colbert's publisher, and the sticker campaign is backed by the American Booksellers Association.)

"We decided not to get down in the mud with everybody else," Sindelar said. "I'm tired of defining ourselves in terms of being different from Amazon. I thought this was a healthy, positive way to show how we operate and what we value."

Sindelar's efforts to gain at the expense of a major rival like Amazon could also be described in another healthy, positive way: competition. Amazon's decision to take a hard line with Hachette seems to have provided a sudden competitive advantage for other booksellers, large and small.

On Walmart.com on Thursday, "The Silkworm" was one of three books featured on the books' home page at 40 percent off, or $16.80. Walmart has also promoted the book with ads on Facebook and through mass emails to its customers promoting Hachette books. On Barnes & Noble's site, "The Silkworm" was one of four of "the week's biggest books." A digital edition for the Nook was $11.99. It was Barnes & Noble's No. 2 best-seller Thursday. On Bookish, the website that the major publishers started last year to combat Amazon, it was the first "new and notable" release featured, and was selling for $19.60.

Amazon showed no sign of backing down. On Thursday, it was selling "The Silkworm" in hardback for $25.20 - nearly the full suggested retail price - along with the message that delivery could take "2 to 4 weeks." On Thursday afternoon, the book's best-seller rank was just 210. (The Kindle digital edition was $9.99.)

From Sindelar's perspective, his promotion was successful. He said he sold 60 copies on the first day, when ordinarily, he said, he'd be lucky to sell five.

All of this must be warming the hearts of antitrust regulators at the Justice Department, which was widely criticized after it filed an antitrust case against five major publishers and Apple, accusing them of conspiring to raise e-book prices. The five publishers - Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin and Simon & Schuster (all the so-called majors except Random House) - settled the charges with the department and agreed not to collude. Apple was found guilty after a lengthy trial. (It is appealing the decision.) A spokeswoman for the Justice Department declined to comment on the Amazon-Hachette dispute.

To many, especially publishers, authors and booksellers, it seemed perverse that the government sued the major publishers and Apple, whose iBookstore was a new entrant into digital publishing, and not Amazon itself, which seemed to be rapidly amassing quasi-monopoly power in book retailing. But as U.S. District Judge Denise Cote in Manhattan ruled, the evidence was overwhelming that the publishers' and Apple's goal wasn't to promote competition, but to raise e-book prices so that Apple wouldn't lose money and so that e-book sales wouldn't undercut the far more profitable sales of hardcover books.

She noted that monopoly power isn't illegal unless it's gained unlawfully, in which case the publishers and Apple should have filed a complaint with the government rather than conspiring to raise prices.

(Also see: Apple Settles Ebook Antitrust Case with US States and Other Complainants)

"Another company's alleged violation of antitrust laws is not an excuse for engaging in your own violations of law," she ruled. "Antitrust laws were enacted for the 'protection of competition, not competitors,'" she continued, quoting a famous Supreme Court case.

Still, even Amazon seems willing to make some concessions. Two Hachette books, J.D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye" and "The Goldfinch," by Donna Tartt, are available on Amazon at deep discounts and for immediate delivery. Why that would be the case isn't clear, but one is a classic used in many schools and the other recently won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

The next big test for Hachette and Amazon will probably come next week, when the Hachette subsidiary Little, Brown will publish "Invisible" by the mega-best-selling author James Patterson and the novelist David Ellis. The book isn't available for preorder on Amazon, although a free 28-page preview is available to Kindle readers.

Amazon confirmed on its website that it was not taking preorders for Hachette books. In its statement, it said that it was "the right of a retailer to determine whether the terms on offer are acceptable and to stock items accordingly."

Hachette declined to comment on negotiations with Amazon. As for "The Silkworm," a spokeswoman for Little, Brown said it was too soon to have any sales numbers, but "the early feedback we've had from retailers is very encouraging."

And while Hachette is the lone publisher operating in the United States in the current standoff, other contracts between Amazon and major publishers will soon be expiring. The other publishers and booksellers are eager to see if they, too, hold the line. (There's nothing illegal about publishers adopting similar stances in their negotiations, as long as they don't collude.)

Whether even the combined efforts of the publishers and competitive efforts of rival retailers can dent Amazon's market power remains to be seen. Amazon accounts for about a third of book sales in the United States and 60 percent of Hachette's digital sales. The person involved in the Hachette negotiations wasn't optimistic for the publishers. In previous rounds with Amazon, "We had so little leverage. It felt like I had a slingshot and they had a tank. We'd fight and fight and then we'd make concessions. They rolled over us."

This person compared Hachette's situation to that of gazelles, a reference to Brad Stone's book about Amazon, "The Everything Store." In it, Stone describes what was known inside the company as "The Gazelle Project," in which the chief executive, Jeffrey Bezos, compared Amazon to a cheetah hunting weak, sickly gazelles - in that case, a metaphor for small publishers.

"Who's going to blink first?" mused Sindelar, the independent bookseller. "That's what everyone wants to know. I have no idea. But a lot of our customers told us they were buying from us explicitly as a protest against Amazon. We live in Seattle, where people go to farmers' markets. They don't want to limit the diversity of where they shop. I think this has helped people realize that if Amazon is the only option, that's putting way too much power in one company."

© 2014 New York Times News Service

For details of the latest launches and news from Samsung, Xiaomi, Realme, OnePlus, Oppo and other companies at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, visit our MWC 2026 hub.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Realme C83 5G

- Nothing Phone 4a Pro

- Infinix Note 60 Ultra

- Nothing Phone 4a

- Honor 600 Lite

- Nubia Neo 5 GT

- Realme Narzo Power 5G

- Vivo X300 FE

- MacBook Neo

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- Tecno Megapad 2

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Tecno Watch GT 1S

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)