- Home

- Internet

- Internet Features

- Up or Down at Dropbox? It's Hard to Say

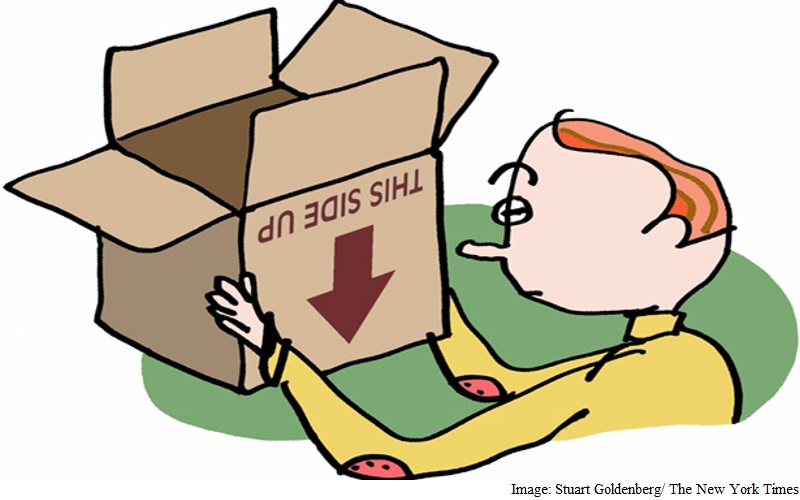

Up or Down at Dropbox? It's Hard to Say

But that isn't the image of Dropbox you'd encounter in the news media. Two years ago, the company raised a round of financing that valued it at $10 billion (roughly Rs. 67,817 crores), making it one of the most highly prized startups of the tech boom. Now it faces a stock market that has turned unfriendly to initial public offerings of tech companies, not to mention stiff competition from publicly traded companies like Microsoft, Google and Box, the similarly named firm in a similar line of business.

As a result, Dropbox's valuation has been battered by a series of "markdowns" from large investors who appear to have turned skeptical about its future. For instance, the mutual fund manager T. Rowe Price now considers Dropbox's shares to be worth half what they were at the time of the last fundraising round.

So what's really going on at Dropbox? Is it thriving or dying?

Neither one, yet. When you look inside the company, you find something that defies Silicon Valley's typical straight-up or straight-down narrative: a complicated story of incremental and potentially accelerating success, but one clouded by outsize dreams of yesteryear.

It's a fate that other Silicon Valley startups may be facing, especially with the dip in public and private markets for funding tech ventures.

Dropbox's problems have less to do with the strength of its current business than with a delay, so far, in realizing the towering expectations that once surrounded the company. The startup is like the college basketball star who manages to turn pro but is still regarded with doubt because everyone has now realized he might never be the next LeBron James. What happens to a company once thought to be worth $10 billion when it turns out to be worth only $5 billion (roughly Rs. 33,908 crores), or $2 billion (roughly Rs. 13,563 crores)?

According to Dropbox's executives, nothing too terrible - it can just wait out the market freeze and perhaps grow into its $10 billion valuation. In other words, Dropbox can keep working and may yet turn into LeBron.

"Sentiment about companies goes in cycles," Drew Houston, Dropbox's co-founder and chief executive, told me in an email. "Google, Apple, Facebook all went through multiple rounds of this. First, you can do no wrong, then you can do no right. Then people are like, 'Actually this is a pretty good company,' and around it goes. So you have to ignore the noise and stay focused on building great products and making customers happy. The rest will take care of itself."

At the moment, executives said, Dropbox isn't in any urgent danger. If it were running out of money, it might be forced to raise funds at a lower value than its previous one - a dreaded "down round" - but executives and board members said the company had plenty of money in the bank and was generating enough from operations to fund an expansion into new products and services.

Other numbers are also promising, they said. More than 400 million people use the company's service - a place to keep documents online, so they can easily be shared and synchronized among different people and different computers - and the service is adding 10 million users a month. Dropbox also has 150,000 business customers, who pay annual fees of about $150 for each employee, and those ranks are growing by about 25,000 businesses a quarter.

Insiders declined to specify Dropbox's revenue and growth rate, other than to say there had been increases since its last funding round, when the company's annual revenue was reported to be $400 million (roughly Rs. 2,712 crores).

Executives also said employee retention and hiring have not been hurt by the recent news. I asked several tech recruiters if they had noticed a diminished interest in working for Dropbox; none had. In the last year, Dropbox has hired from Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Twitter.

"Dropbox is growing on the same trajectory as the best software-as-a-service companies ever - like LinkedIn or Salesforce," said Bryan Schreier, a Dropbox board member and a partner at the investment firm Sequoia Capital, which has invested in the company. "I don't know how we couldn't be thrilled with that kind of performance."

But if Dropbox can still thrill its backers, it has also accumulated a chorus of skeptics. The company is one of several looking to ride two tidal waves now sweeping the business world - the trend toward business software that doesn't stink, known as the "consumerization of information technology," and the rising willingness of companies to store their most precious data on online servers, or in the cloud.

Dropbox's issue is that its products for business customers are relatively new compared with those of its rival Box, which was founded before Dropbox and began focusing on business users earlier. Dropbox is behind Box in attracting the most lucrative segment of the market - the largest companies who will pay the most to get their data online.

Adding to this is the complication that Box, which has had to spend hundreds of millions of dollars building out a sales team to go after large companies, has been pummeled by investors for its persistent losses. The stock market now values Box at about $1.3 billion (roughly Rs. 8,816 crores), about half of its value when it went public in January 2015.

This sets up an unfavorable comparison for Dropbox: If Dropbox trails Box in the meatiest part of the market, and if Box is itself losing money, how can Dropbox possibly be worth 10 times as much as Box?

Dropbox argues that comparison with Box doesn't take into account the differences in the two companies' business models. Sure, Dropbox is developing its sales team and expanding its product offerings for businesses. But Dennis Woodside, Dropbox's chief operating officer, said that its broad brand recognition makes the sales process more efficient - and thus cheaper - than Box's.

When Dropbox visits a company's chief information officer on a sales call, it has something Box struggles to show - a large base of the company's employees who are already using its service.

"We fish in a pond that's used to our product," Woodside said.

In the last quarter, Dropbox signed up 13 large companies with more than 1,000 users each, he said, three times as many as in the same period last year.

Schreier of Sequoia Capital said Dropbox's potential for profit was more attractive than Box's, and argued that when Dropbox eventually goes public, investors will recognize that difference.

Aaron Levie, Box's chief executive, disputed this assertion. "Our differentiation and maturity in the enterprise market is what wins those customers," he said.

A large and costly sales team also makes a difference, Levie argued, which is why he seemed to scoff at the notion of Dropbox as a competitor. "We're mostly competing with Microsoft in the enterprise, not Dropbox," he said.

Because one company is public and one is private, and because they operate so differently, it is difficult to say whether Box or Dropbox - not to mention Google or Microsoft - will ultimately run away with the enterprise cloud services business. Analysts say that at the moment, the market is big enough, and wide open enough, for all of these companies to thrive.

The murkier issue is not whether Dropbox can build a good business, but whether it can ever become the $10 billion goose that investors had once seen it as. Reports of Dropbox's demise are premature. But so are reports of its comeback.

© 2016 New York Times News Service

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025

- ChatGPT

- Redmi Note 14 Pro+

- iPhone 16

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- OPPO A6v 5G

- OPPO A6i+ 5G

- Realme 16 5G

- Redmi Turbo 5

- Redmi Turbo 5 Max

- Moto G77

- Moto G67

- Realme P4 Power 5G

- HP HyperX Omen 15

- Acer Chromebook 311 (2026)

- Lenovo Idea Tab Plus

- Realme Pad 3

- HMD Watch P1

- HMD Watch X1

- Haier H5E Series

- Acerpure Nitro Z Series 100-inch QLED TV

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)