- Home

- Internet

- Internet Features

- Privacy Policies With an Escape Hatch

Privacy Policies With an Escape Hatch

The privacy policy for Hulu, a video-streaming service with about 9 million subscribers, opens with a declaration that the company "respects your privacy."

That respect could lapse, however, if the company is ever sold or goes bankrupt. At that point, according to a clause several screens deep in the policy, the host of details that Hulu can gather about subscribers - names, birth dates, email addresses, videos watched, device locations and more - could be transferred to "one or more third parties as part of the transaction." The policy does not promise to contact users if their data changes hands.

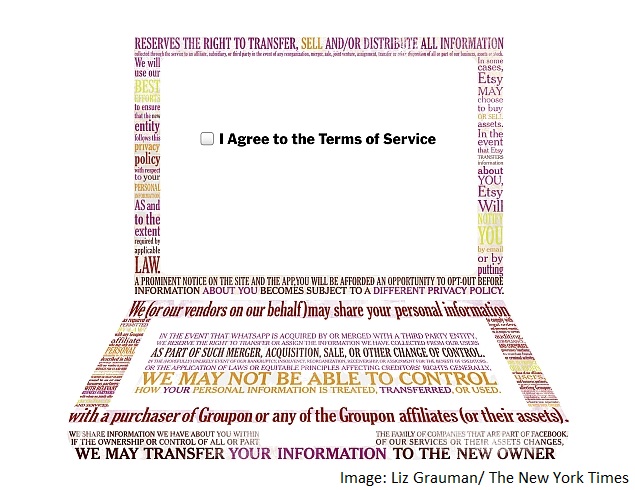

Provisions like that act as a sort of data fire sale clause. They are becoming standard among the most popular sites, according to a recent analysis by The New York Times of the top 100 websites in the United States as ranked by Alexa, an Internet analytics firm.

Of the 99 sites with English-language terms of service or privacy policies, 85 said they might transfer users' information if a merger, acquisition, bankruptcy, asset sale or other transaction occurred, The Times' analysis found. The sites with these provisions include prominent consumer technology companies like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and LinkedIn, in addition to Hulu.

"It's 'we are never going to sell your data, except if we need to or sell the company,'" Hal F. Morris, the assistant attorney general of Texas, said about industry practices.

Hulu declined to comment.

Sites, apps, data brokers and marketing analytics firms are gathering more and more details about people's personal lives - from their social connections and health concerns to the ways they toggle between their devices. The intelligence is often used to help tailor online experiences or marketing pitches. Such data can also potentially be used to make inferences about people's financial status, addictions, medical conditions, fitness, politics or religion in ways they may not want or like.

When sites and apps get acquired or go bankrupt, the consumer data they have amassed may be among the companies' most valuable assets. And that has created an incentive for some online services to collect vast databases on people without giving them the power to decide which companies, or industries, may end up with their information.

"In effect, there's a race to the bottom as companies make representations that are weak and provide little actual privacy protection to consumers," said Marc Rotenberg, the executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a non-profit research centre in Washington.

The potential ramifications of the fire sale provisions became clear two years ago when True.com, a dating site based in Plano, Texas, that was going through a bankruptcy proceeding, tried to sell its customer database on 43 million members to a dating site based in Canada. The profiles included consumers' names, birth dates, sexual orientation, race, religion, criminal convictions, photos, videos, contact information and more.

Because the site's privacy policy had promised never to sell or share members' personal details without their permission, Texas was able to intervene to stop the sale of customer data, including intimate details on about 2 million Texans.

"That is the type of information that people were entitled not to have trafficked and sold to the highest bidder," said Morris, the Texas assistant attorney general. "I think it's an important safety issue for consumers."

If privacy policies contain unrestricted data-transfer provisions, however, consumers and government authorities have little recourse.

Among the top 100 sites in the Times analysis, at least 17 said they would alert consumers - by, for example, posting a notice on their site - if users' personal details changed hands. But only Etsy, the crafts e-retailer, Weather.com and a few other sites promised to allow people to opt out of having their data handed over to a third party in certain circumstances.

Jordan Breslow, Etsy's general counsel, said that enabling the site's members to control their personal information tallied with the company's values of respect for consumer trust.

(The privacy policy of The New York Times says that, in the event of a business transaction, consumers' information may be included among transferred assets. It does not promise to notify users if such a situation were ever to occur.)

After one data-driven service buys another, it can leave consumers questioning how their details will be used. Unless the company has made a previous promise to inform them, or the data is specifically regulated by a law like the federal Video Privacy Protection Act, sites and apps generally do not need to be notified about transfers of their information.

Last year, for instance, Facebook bought WhatsApp, the stand-alone messaging service, for nearly $22 billion. Subsequently, some people who regularly used both services, like Neil Kirkpatrick, a digital project manager in Berkhamsted, England, began to notice some odd coincidences.

"Added someone to my iPhone contacts to chat on @WhatsApp and now Facebook is recommending them as a friend," Kirkpatrick wrote on Twitter recently.

In a phone interview, Kirkpatrick said he had not permitted Facebook access to his contact list and had set his Facebook profile to prevent people outside his network from using his phone number to locate him. So he did not understand how Facebook could have connected him to new contacts on WhatsApp.

"They could do a lot more to be upfront and honest about what information they have on you and where they are getting it," Kirkpatrick said. "It doesn't feel like you are in control of your own data."

Jonathan Thaw, a Facebook spokesman, said Facebook did not use contact information from WhatsApp. He added that Facebook used a variety of factors - such as mutual friends, work and education information - to suggest friends.

WhatsApp did not respond to emails seeking comment.

Some sites first adopted fire sale clauses after the Federal Trade Commission in 2000 sued Toysmart.com, a bankrupt online toy retailer, for deceptive practices regarding data gleaned from its site visitors. Toysmart was seeking to sell customer details - including their children's names and birth dates - even though the company's privacy policy had promised never to share that information with third parties.

In an effort to avoid similar complaints, other sites began claiming the right to sell or share user data as part of business transactions.

It's a trend that is likely to widen as companies introduce new Internet-enabled products, like connected cars and video cameras, which can collect and transmit a constant stream of data to the cloud.

Rather than wade through companies' data-use policies before registering with websites, however, many people simply click the agree button.

"I think society views it as what you have to do to get to the next page of the website," said Elise S. Frejka, a lawyer who served as the consumer privacy ombudsman in the recent RadioShack bankruptcy case.

But reading through a site's data-sharing policies can be a confounding experience.

One example is Nest, an Internet-connected thermostat company that enables people to control their home energy use via their mobile devices. Acquired by Google for $3.2 billion (roughly Rs. 20,432 crores) last year, Nest has different online privacy pages with seemingly conflicting statements.

One page, in colloquial English, says that the company values trust: "It's why we work hard to protect your data. And why your info is not for sale. To anyone."

Another page, containing Nest's official privacy policy, however, says: "Upon the sale or transfer of the company and/or all or part of its assets, your personal information may be among the items sold or transferred."

In an email, Alexandra Zoz Cuccias, a Nest spokeswoman, said the two statements were "not contradictory."

The information on the first page, she wrote, "is meant to be very clear and explain how we think about privacy, in part by helping users understand how our business does and does not work." For instance, she said, Nest does not sell its customer lists to third parties.

In the actual privacy policy that indicates that customer data may be included as part of a company asset sale, she said, "we provide a necessarily more detailed discussion to users about the specific ways Nest uses and processes data."

© 2015, The New York Times News Service

For details of the latest launches and news from Samsung, Xiaomi, Realme, OnePlus, Oppo and other companies at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, visit our MWC 2026 hub.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Realme C83 5G

- Nothing Phone 4a Pro

- Infinix Note 60 Ultra

- Nothing Phone 4a

- Honor 600 Lite

- Nubia Neo 5 GT

- Realme Narzo Power 5G

- Vivo X300 FE

- MacBook Neo

- MacBook Pro 16-Inch (M5 Max, 2026)

- Tecno Megapad 2

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Tecno Watch GT 1S

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)