- Home

- Games

- Games News

- Hunting for an 'E.T.' game in a most terrestrial place

Hunting for an 'E.T.' game in a most terrestrial place

You load the cartridges into trucks and bury them in the New Mexico desert.

Atari did just that almost 30 years ago, or so the story goes. The truth lies beneath packed dirt and poured concrete in a sleeping landfill by the railroad tracks behind a McDonald's here, where this city of about 32,000, home to an Air Force base and the state's Space History Museum, dumped its garbage many years ago.

A spray-painted sign, bright orange against a white background, warns visitors: "Keep Out."

The place may be the final resting place for the video game "E.T.," recalled by some as one of the worst video games ever made.

Snopes.com, the Web authority on rumors, hoaxes and urban myths, ruled the burial of the "E.T." cartridges a legend, though there are enough stories circulating online to cast doubt and feed the mystery. Here - in plastic cases, shoe boxes and tattered paper bags stored in closets and garages - there is enough proof to be found that at least some "E.T." games were buried in the landfill.

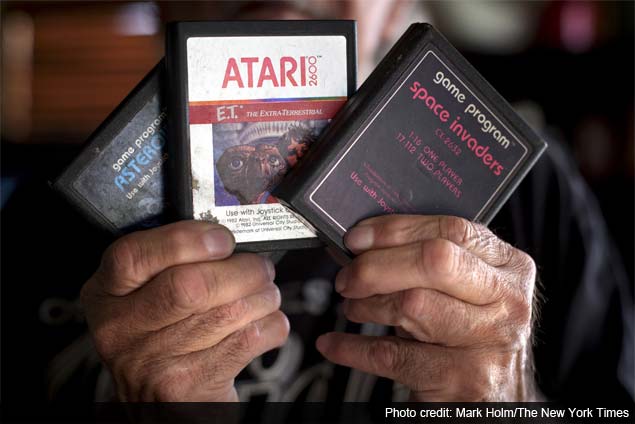

"It's not a myth," Mark Esquero, 69, said in his living room one recent afternoon, brandishing a cartridge of "E.T.," one of more than a dozen games he scooped from a deep hole in the landfill the night after Atari dumped its loot.

The event has captured the imagination of the original joystick generation, to whom the video game experience was grounded on the enchanting possibilities of rudimentary graphic designs. (Think of characters built with Lego bricks; no curved lines.) It has inspired music videos and an independent film based on the Web television series "The Angry Video Game Nerd," whose main character, traumatized by the "E.T." game, sets out to debunk the legend of the landfill, hoping to save young generations of gamers from the trauma of playing it.

"Everybody's always fantasized about digging up those games," James Rolfe, the filmmaker and star of the series, said in an interview. "It's the perfect nerdy treasure hunt."

What could be there?

"Systems, prototypes," said Joe Lewandowski, who ran a waste-management company in Alamogordo in the 1980s and seems to know a lot more about what happened than he is willing to tell. (Further questions were met with a mix of silence and mischievous smiles.)

Readers of a certain age might remember Geraldo Rivera's quest to uncover the secrets of Al Capone's vaults in 1986, a live television event that spectacularly revealed nothing besides empty bottles and debris. Last month, Fuel Entertainment, a digital company in Los Angeles, acquired an exclusive permit to excavate the Alamogordo landfill over the coming six months. It is probably safe to say there is going to be more than dust to find.

"We're 100 percent going to be digging," assured the company's chief executive, Mike Burns, though he cautioned that "there might be nothing" in the hole or "there might be the holy grail of video games."

There is no definitive account of that day in September 1983 when the trucks brought the Atari haul here, just versions that seem to feed on one another, changing slightly as they travel from one online forum to the next, as in a virtual game of telephone.

One story put the number of trucks at 20. Others say there were 10 or 14. Lewandowski recalled last week that 29 trucks had left Atari's plant in El Paso, Texas, just over the border from New Mexico, and that nine had made it to the landfill.

"The other 20," he said, "no one knows what happened."

There is a lingering rumor that one of the trucks was hijacked along the way and taken to Mexico, never to be seen again.

"E.T.," the video game, was made in five weeks so it could hit the market in time for the 1982 Christmas shopping season. Atari was banking on cashing in on the blockbuster movie "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial," and paid Steven Spielberg, its director and co-producer, $20 million to $25 million for the rights to the film's name.

Nick Montfort, an associate professor of digital media at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a co-author of "Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System," said, "It seems really impossible that anyone could have made a good game in that amount of time."

The game was a huge flop. More than half the 5 million cartridges made were returned.

"E.T." was not Atari's only mistake. The company made more "Pac-Man" cartridges than there were consoles at the time, Montfort said, "like making more records than there are record players." Besides, it lost its hegemony once competitors began making cartridges that fit its system - some of them better than Atari's, others cheaper but just not good.

"The market got oversaturated by stuff nobody wanted," said Andrew Reiner, executive editor of Game Informer, a monthly magazine based in Minneapolis.

City officials here see the impending excavation of the landfill as an opportunity. One commissioner, Jason Baldwin, 39, said, "Any exposure is good exposure." Another, Jim Talbert, 64, said, "I don't understand what the fuss is all about, but we welcome it."

Mayor Susie A. Galea, 32, said, "If you look at Roswell," the city 120 miles to the east where a UFO is rumored to have crash-landed in 1947, "it has a theme. Alamogordo doesn't. We're not sure what we want to be."

Her hope, Galea went on, is that "the dig turns us into a destination, regardless of what it is that they find in there."

© 2013, The New York Times News Service

PS4 vs. Xbox One: The next gen gaming wars

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Tecno Pova Curve 2 5G

- Lava Yuva Star 3

- Honor X6d

- OPPO K14x 5G

- Samsung Galaxy F70e 5G

- iQOO 15 Ultra

- OPPO A6v 5G

- OPPO A6i+ 5G

- Asus Vivobook 16 (M1605NAQ)

- Asus Vivobook 15 (2026)

- Brave Ark 2-in-1

- Black Shark Gaming Tablet

- boAt Chrome Iris

- HMD Watch P1

- Haier H5E Series

- Acerpure Nitro Z Series 100-inch QLED TV

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)

![[Partner Content] OPPO Reno15 Series: AI Portrait Camera, Popout and First Compact Reno](https://www.gadgets360.com/static/mobile/images/spacer.png)