Using Google Maps May Reduce the Amount of Gray Matter in Your Brain

Eventually, the center has resorted to installing a large sign at the front of their driveway instructing travelers that their electronic devices are wrong about Mt. Rushmore's location. Despite this, guest services manager Ashley Wilsey told the Kansas City Star that she regularly encounters a near-constant flow of tourists mistakenly navigating to the center.

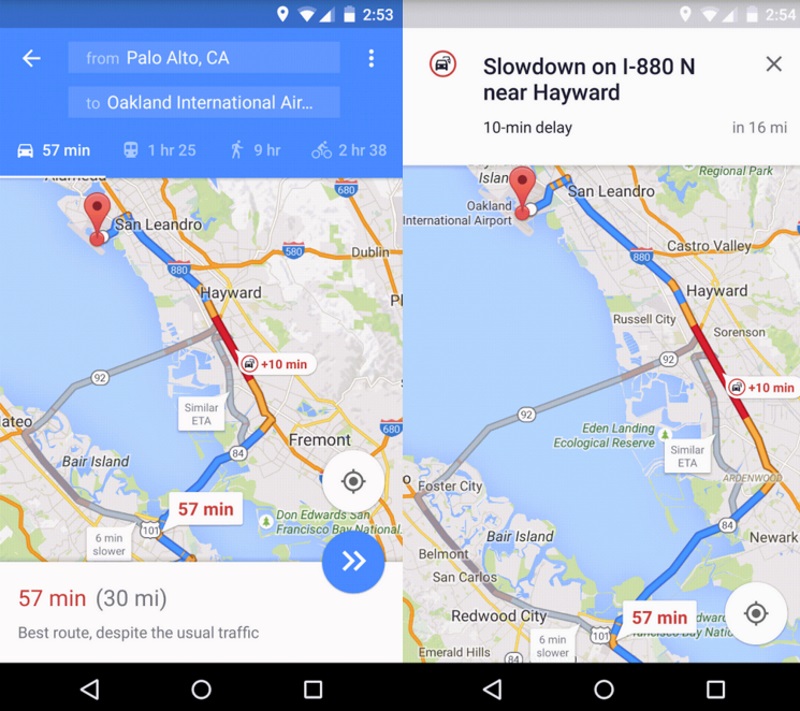

Although Google Maps is fast becoming the ultimate authority on navigation, the program is proving vulnerable to mistakes and hackers with results that at times can be catastrophic.

One of the latest blunders involved a company accidentally bulldozing the wrong house due to faulty Google Maps directions. Google took responsibility for the maps error. In this case, two different houses were shown as being in the same location, a Google spokeswoman told CNN.

Then there was the case of a seemingly random Wisconsin murder that investigators say might be due to a Google Earth mix up. Police say that they discovered that the murdered couple's address was switched with another house on the online map - that of the president of a local bank who had received death threats. In 2010, Nicaragua blamed an accidental invasion of Costa Rica on incorrect Google Maps information.

(Also see: Google Maps Needs to Learn More About India)

These cases shed light on the software's susceptibility to errors and hacks. Google Maps is built on layers on information obtained from satellite images as well as photographs taken by Street View cars, which have driven and photographed more than 7 million miles of roads. Google also crowdsources location information through Map Maker, which allows users to directly update local addresses and details. An unknown number of people are employed by the company to comb through these maps for inaccuracies.

But despite this multi-faceted system, location bugs and mistakes still happen. Trolls and pranksters have taken advantage of the crowdsourced feature by changing businesses to offensive names or by doodling on the map interface. One showed the mascot for Google's mobile operating system, Android, urinating on the Apple logo in an area of Pakistan.

More explicit hacks have also proved that Google Maps is easily accessible to outsiders. Bryan Seely revealed vulnerabilities in Google Maps in 2014 when he hacked into Google Map's business listings and changed the phone number for the San Francisco FBI office and Washington D.C. Secret Service. In a Gizmodo article, Seely described a world of con artists who exploit the feature's vulnerabilities with ease by switching business listings and conning unsuspecting callers. He blames Google's less-than-stellar verification system. "Who is gonna think twice about what Google publishes on their maps? Everyone trusts Google implicitly and it's completely unwarranted and it's completely unsafe," Seely told Valleywag in an interview last year. He also mentioned that he has been paid by companies like Microsoft to spam Google Maps in the past.

Then there's the human error element, such as the case of American tourist, Noel Santillan, who drove six hours in the wrong direction in Iceland through wintery conditions due to a small spelling error he entered into Google Maps. For those misguided Mt. Rushmore tourists, even a large metal sign instructing them to turn around couldn't deter them from total GPS obedience. Some researchers have suggested that GPS dependence is becoming more and more common, and are worried about unforeseen effects. Are we collectively losing our learned sense of direction?

Neuroscience studies suggest that yes, Google Maps and GPS systems may indeed be negatively impacting our brains. Research at McGill University compared the brains of GPS versus non-GPS users and found that non-GPS users had more gray matter and higher functionality in their hippocampuses than those that relied on their devices. The hippocampus is responsible for memory and spatial navigation, the latter of which uses visual cues to create a cognitive map that assists with directionality. An earlier study showed that London taxi drivers, well-versed in the complex map of the city, had much larger hippocampuses than non-taxi drivers. There is also some correlation between those with a more developed hippocampus and lower chances of Alzheimers.

Veronique Bohbot, a neuroscientist who worked on McGill's GPS study, suggests that we limit our GPS use to new destinations only and attempt to build up our cognitive maps by navigating to frequently visited destinations on our own, she said in an article on Phys.org.

Given recent errors, our memories might wind up being more accurate than Google Maps itself.

© 2016 The Washington Post

For the latest tech news and reviews, follow Gadgets 360 on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News. For the latest videos on gadgets and tech, subscribe to our YouTube channel. If you want to know everything about top influencers, follow our in-house Who'sThat360 on Instagram and YouTube.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025

- ChatGPT

- Redmi Note 14 Pro+

- iPhone 16

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Infinix Note 50s 5G+

- Itel A95 5G

- Samsung Galaxy M56 5G

- HMD 150 Music

- HMD 130 Music

- Honor Power

- Honor GT

- Acer Super ZX Pro

- Asus ExpertBook P3 (P3405)

- Asus ExpertBook P1 (P1403)

- Moto Pad 60 Pro

- Samsung Galaxy Tab Active 5 Pro

- Oppo Watch X2 Mini

- Garmin Instinct 3 Solar

- Xiaomi X Pro QLED 2025 (43-Inch)

- Xiaomi X Pro QLED 2025 (55-Inch)

- Nintendo Switch 2

- Sony PlayStation 5 Pro

- Toshiba 1.8 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (RAS-24TKCV5G-INZ / RAS-24TACV5G-INZ)

- Toshiba 1.5 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (RAS-18PKCV2G-IN / RAS-18PACV2G-IN)